Buck Canel: the voice of ‘béisbol’ throughout Latin America

The first time I saw broadcaster Eloy “Buck” Canel was at Atlanta Stadium several days before the 1972 All-Star Game. He was sitting alone in the press box about two hours before that evening’s game.

I had listened to his broadcasts since my childhood and, in my mind, he was part of my life. Therefore, I didn’t hesitate to walk up to him and say, “Mr. Canel, I know who you are. Can I shake your hand?”

The man with a lively personality gave me a smile, and in his unique, deep rasp of a voice replied, “The honor is mine.”

Our friendship was largely cemented that day. He even he asked me about a relative of mine, Radamés Mayoral, who for many years was the voice of the Leones de Ponce in the Puerto Rico Winter League.

Buck Canel was born in Rosario, Argentina, on March 4, 1906. His father was a career diplomat and his Argentine mother a journalist. A man of the world, he grew up in his native country and in Staten Island, N.Y., while spending time as a young adult in Cuba, where he could trace some of his family roots.

When we met, he was 66 years old and had broadcast Major League Baseball games since 1936, predominantly for the New York teams — Brooklyn Dodgers and then the Yankees and Mets — and Latin American Spanish-language markets by way of the internationally syndicated Cabalgata Deportiva Gillette, NBC’s Gillette Cavalcade of Sports, which at its peak aired on more than 200 radio stations.

Señor Hemingway

For years, I called him Ernest Hemingway for his well-kept beard and his penchant for beret-type hats. With deep respect, I used the title Señor Hemingway — and he loved it.

Like Hemingway, he started out as a journalist, writing for the Staten Island Advance. And perhaps better than Hemingway, he was a master of English and Spanish.

Buck told the story of his first broadcast, a rather grand debut, to his friend Tirso Valdez. And in 1985, Valdez recounted that story to New York Spanish-language newspaper, El Diario La Prensa. In Buck’s words:

“It all happened in September 1933… I was the Associated Press correspondent in Havana, Cuba. A revolution led by Fulgencio Batista toppled dictator Gerardo Machado. Days later, Batista asked me if in Miami his speech [minutes earlier] had been heard, and he told me I should translate it… He escorted me to the mic and in front of the media members present, I translated it from Spanish to English… and I did not make an error.”

Poet behind the mic

Canel was an intellectual. He loved to hold court, and like Hemingway, he enjoyed an occasional cocktail while talking about boxing, politics, classical music, arts and literature. His strategic disposition was reflected in two favorite pastimes — playing chess and expressing ideas on how to fix the world.

He was a poet behind the mic, a sonero mayor, what in the world of salsa music is known as a master singer. Canel could keep the beat of a baseball game while improvising stanzas about food, culture and current events. He was whimsical with wordplay and laughed at his own jokes.

He called the seventh inning El inning de la suerte, ¡el Lucky Seven! But the phrase that I still love after all these years is what he usually said as he went to break in a tight game: ¡No se vayan, que esto se pone bueno! “Don’t go away, because this is getting good.” He also happened to be an outstanding boxing announcer.

From the 1970s to the early 1980s, I was part of a broadcast team for WAPA Radio in Puerto Rico covering East Coast teams. Whenever we were in New York, we were honored with his visits to our booth. Spending time with him was like taking a history lesson. Here are some memorable moments from his career:

- He was the only Hispanic member of the media to cover the first Hall of Fame induction ceremony on June 12, 1939, in Cooperstown, N.Y.

- He served as a translator for President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and for the United Nations.

- He was the best man in the wedding of Sonia Llorente and future Hall of Famer Luis Aparicio in 1956.

- He was a writer for the Associated Press, Agence France-Presse (the French news agency) and its predecessor, Agence Havas (the French wire service).

- Starting in 1937, he broadcast 42 World Series, a record which still stands. Funny enough, he complained that it should have been 43, but in October 1964, he was sent to Tokyo to cover the Summer Olympics.

- He treasured friendships with the Venezuelan Aparicio, Puerto Rican Roberto Clemente and Panamanian Rod Carew, all Hall of Famers.

A great raconteur

During the last few years of his life, he would often become reflective when visiting Yankee Stadium. Then, suddenly, he would become alive and energetic when dipping into his vault of great memories.

With a smile, he would recall experiences with Eva and Juan Perón in Argentina; Cuban dictators Fidel Castro and Batista; their Nicaraguan counterpart, Anastasio “Tachito” Somoza; and the Dominican Republic’s Rafael L. Trujillo. And he could easily switch to former U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, the Spanish bullfighter Manolete, or the heavyweight champions Joe Louis, Rocky Marciano and Muhammad Ali.

Like I’ve said, Buck reminded me of Ernest Hemingway. For me, the two great raconteurs were undeniably, inexplicably similar.

One evening during the 1975 Caribbean Series in Puerto Rico, after attending a reception held by Gov. Rafael Hernández Colón at La Fortaleza, the governor’s official residence, Buck suggested that we walk around Old San Juan and visit his favorite restaurant, La Mallorquina, established in 1848.

David Albarrán, a bartender there since the 1940s, recognized Buck and minutes later brought out two remembrance logs dated March 30, 1948, and March 20, 1969.

We found Buck’s signatures, along with those of Gloria Swanson, Nat King Cole, Eddie Fisher and Luis Muñoz Marín, the first popularly elected governor of Puerto Rico. He was truly moved and I saw the joy in his eyes.

Ford C. Frick Award

In 1978, the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum established the Ford C. Frick Award, presented annually to a broadcaster for major contributions to baseball. The first two recipients were Mel Allen, the longtime legendary voice of the New York Yankees; and Red Barber, for 15 years the “Voice of the Dodgers” before becoming Allen’s partner on the Yankees’ broadcasts.

During the course of that year, I undertook the mission of nominating Buck for the award. I started campaigning with numerous calls and letters without positive results until 1980, when Commissioner Bowie K. Kuhn decided to help promote Canel’s candidacy through his own channels.

It coincided with Canel’s passing that year, on April 7. I’ll never forget that week. I was on the air with Guillermo Portuondo Calá, sports director for the USIA Voice of America radio network — informing millions of fans in Latin America of his passing.

Several days later, I got a typed letter from Kuhn dated April 14, saying, “I share your sentiments about Buck Canel. In addition to his professional abilities, he was a great guy. I know I will miss him. I will see to it that your further thoughts on the Ford Frick Award are brought to the attention of the committee.”

In March 1985, prior to a banquet in St. Petersburg, Florida, Bill Guilfoile, then the Hall of Fame’s public relations director, pulled me aside and said, “Your guy, Buck Canel, will be honored this year.”

I felt enormous joy. But this mission did not end there. We had to locate Buck’s widow, journalist Colleen Park, who had moved from their home in Croton-on-Hudson, New York.

Several weeks later, I located her living with her daughter Alice and her daughter’s husband at their Tri-Rivers farm in Moncure, N.C.

On Saturday, July 28, 1985, Colleen, accompanied by her three grandkids — Chip, Nancy and Steve — accepted the award on behalf of her late husband, the first Hispanic so honored.

As I had said in that sad broadcast in 1980 on VOA, “As a writer, Ernest Hemingway conquered readers around the world. His fan and look-alike, Buck Canel, conquered baseball fans internationally with his voice and eloquence behind the mic.”

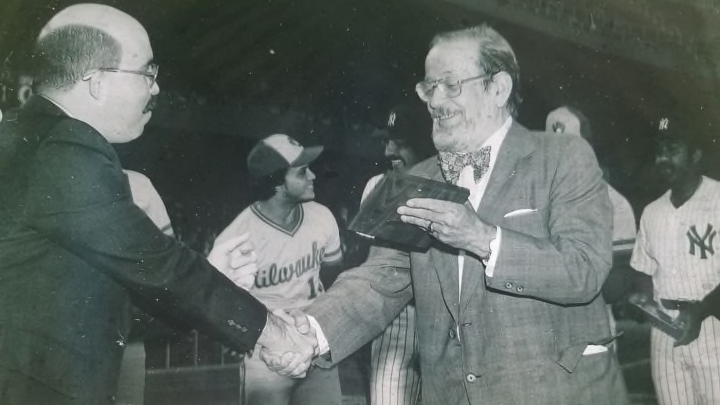

Featured Image: Luis Rodríguez Mayoral

Inset Image: National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum