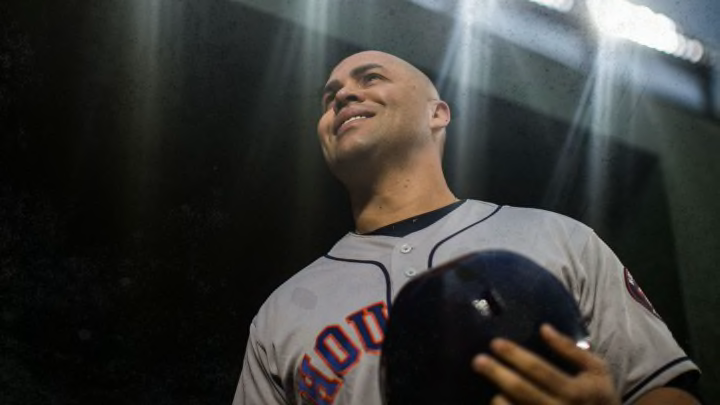

Carlos Beltrán: From Rookie of the Year to Latino Legend

The considerable merits of Carlos Beltrán’s career will certainly be debated thoroughly when he becomes eligible for the Hall of Fame in five years. But after announcing his retirement today in The Players Tribune, there’s no doubt where this switch-hitter extraordinaire stands in the pantheon of Latino legends — he’s the player from Puerto Rico who has come closest to emulating Roberto Clemente on and off the field.

Measured either by his metronomic consistency or new metrics, by his WAR or his post-season exploits, by his baseball advocacy or humanitarian gestures, Beltrán stood apart over the course of 20 seasons, starting with being voted Rookie of the Year in 1999 to winning the coveted Roberto Clemente Award in 2013 to helping the young and talented Houston Astros capture their first World Series title two weeks ago.

“What I most like about Beltrán is his humility,” said Luis Rodríguez Mayoral, a former reporter, broadcaster and Texas Rangers executive who’s now a La Vida Baseball senior writer. “But he was also a complete ballplayer. His statistics speak for themselves. He was a worthy outfielder, a three-time Gold Glove winner, a generational player, a giant of the game.”

Advocate of change

A shy 18-year when drafted out of Manatí, Puerto Rico, by the Kansas City Royals in the 1995 amateur draft, Beltrán made it a point to master English and help other Latinos with their transition to professional baseball and the United States.

One reason why Major League Baseball started providing in 2016 Spanish-language translators for Latin American players years after it did the same for Asian players is that Beltrán persisted with Major League Baseball and the MLB Players Association until he got his way.

When Hurricane María devastated Puerto Rico on Sept. 20, Beltrán immediately pledged $1 million for relief efforts through his Carlos Beltrán Foundation. Even though his baseball academy in Florida, a small town west of San Juan, was flooded by more than four feet of water, a couple of weeks later he opened the doors on weekends to provide thousands of meals to storm victims.

“What an extraordinary gesture, which demonstrates the values we have as Puerto Ricans. It makes me feel very proud,” said Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda in Spanish in an interview with La Vida Baseball. “Carlos is a good friend, a good teammate and a tremendous person.”

Powerful breakthroughs

Along with Clemente, Cepeda set the standards for players from the island. He was the first boricua and second Latino voted ROY, a unanimous National League selection in 1958 after hitting .312 with 25 home runs and 96 RBI for the San Francisco Giants.

The next Puerto Rican to earn this distinction was Benito Santiago, whose historic 34-game hitting streak — still the record for rookies, catchers and the San Diego Padres — made him the unanimous choice in the NL in 1987.

Rounding out the list from Puerto Rico are Cleveland catcher Sandy Alomar Jr., the unanimous AL ROY choice in 1990; followed by Beltrán, who got 26 of 28 votes in 1999; and Carlos Correa, Beltrán’s teammate this season on the Astros, who edged out countryman and fellow shortstop Francisco Lindor, 17-13, in 2015.

Each one of these players sparkled for different reasons, but from the beginning Beltrán was the epitome of the five-tool player, smooth and swift. Rodríguez Mayoral met Beltrán for the first time in 1999 when the Rangers were playing in Kansas City. Without waiting for an introduction, he approached Beltrán in the dugout.

“I went straight up to him and told him that you had the talent, you’re here already, so just do things the right way and God will be with you,” Rodríguez Mayoral said. “And he looked at me funny, not really expecting those words. I basically told him, ‘don’t screw up.’ But they impacted him in a positive way. Roberto Clemente was like that. Clemente wasn’t perfect, but you knew that he had something innate. The same with Carlos. Clemente and Beltrán are both special people.”

Different kind of leader

Beltrán never led a category in a season except for games played in 2002. But he led in the clubhouse, and like Clemente and Cepeda, always rose to the occasion. In plain metrics, during 20 seasons with seven different teams, he hit .279/.350/.486 with 435 home runs and 1,587 RBI, achieving a 69.8 WAR.

But if you want context, he’s one of four players with more than 2,500 hits, 400 home runs, 300 stolen bases and an .810 OPS. The other three? Willie Mays, Barry Bonds and Álex Rodríguez.

A centerfielder turned right fielder turned DH, Beltrán stood tall at both sides of the plate, keeping his body quiet and straight while swinging easy. Only three switch-hitters blasted more home runs — Mickey Mantle, Eddie Murray and Chipper Jones. Mark Teixeira is the only other switch-hitter to reach 400 dingers.

Beltrán was thrown out stealing only 49 times in 20 years. His 86.4 percent success is the highest for players with at least 200 steals. At his peak, there was no better all-around player.

And while there are still New Yorkers who won’t forgive Beltrán for not swinging at Adam Wainwright’s 12-to-6 o’clock curveball that ended the 2006 NLCS between the New York Mets and St. Louis Cardinals, he still averaged .307 and hit 16 home runs in postseason play.

When the Astros brought back Beltrán this season at age 40, they agreed to pay him $16 million. For a team that is driven by analytics more than any other club, someone in the front office was prescient and made a decision based on human dynamics. They added a player who would teach their young core of stars how to win.

Among the first things Beltrán did was to ask Correa and second baseman José Altuve to dinner. He also requested a locker in the middle of the clubhouse. Beltrán, drawing on two decades of experience, kept it real and loose. He bought two championship belts and made the team vote after each victory for the position player and pitcher of the game. He wanted the Astros to embrace the moment, and they celebrated their triumphs with party lights and a fog machine. No wonder they won 101 times during the regular season.

Class closing act

Beltrán, who wore down over the season, played little during the playoffs. But the two times the Astros faced adversity, he got credit for the save. When they were down 3-2 to the Yankees in the ALCS, Beltrán gave a speech. A casual one, he said, enough to lighten the mood and allow the Astros to relax and come back at home, advancing to the Fall Classic for the second time in their history.

And when Cuban first baseman Yuli Gurriel made a racist gesture to Japanese pitcher Yu Darvish in Game 3 of the World Series, it was Beltrán who addressed the situation and advised Gurriel about how to make amends. Working as an intermediary between Gurriel and Darvish, a former teammate on the Rangers, Beltrán helped turn an ugly incident into a teaching moment highlighted by Darvish’s magnanimous tweet of forgiveness.

Beltrán is retiring as a player, but may not be done with the game. He said today that he would like to manage and even interview for the Yankees’ vacancy. There’s a certain irony in that; Clemente was preparing himself to manage at the end of his career. He never got his chance due to his tragic death in an airplane accident. But Beltrán, like he has for most of his professional life, is following in the footsteps of the patron saint of Latino players. He’s doing what Clemente wanted to do.

“All the Puerto Ricans who make it to Major League Baseball are inspired by Roberto Clemente. That’s a given,” Rodríguez Mayoral said. “But Beltran’s character elevated him. No one has ever said a bad word about him. And that’s across the spectrum. That’s a reflection of his upbringing, of what he was taught at home. After a 20-year career, it’s sad to see a player like him leave the game.”

Featured Image: Rob Tringali / Sportschrome / Getty Images Sport