The next chapter for Carlos Beltrán

Carlos Beltrán had just put the finishing touches on a breathtaking 20-year career, which ended on a crescendo that others could only dream about: a 2017 world championship with the Astros that stood alongside his 435 home runs, 2,725 hits and three Gold Glove awards.

To say Beltrán walked away as an industry giant barely covers it. He’ll be a strong candidate for first-ballot induction into the Hall of Fame in 2022, at which point those numbers will look irresistible. But there was another number that mattered to Beltrán after the final out of the ’17 World Series. He was in his age-40 season and very ready to retire.

“I’d had enough, God gave me a great career and I took the most out of it,” Beltrán said. “I squeezed that towel until the last drop and I was happy to go home. Happy to be with my kids.”

Beltrán was staring at that wide open space called the rest of his life, a beautiful horizon with limitless possibilities. He could’ve returned to his native Puerto Rico or kept the family in New York where he’d played for both the Mets and Yankees. Door Number three was a second career in baseball, this time in the front office.

It wasn’t long after Beltrán had retired that Yankees general manager Brian Cashman called to gauge the slugger’s interest in managing the Bombers. The executive knew Beltrán had no prior experience in the dugout, but it was Beltrán’s maturity, his standing among his peers, not to mention his insider’s knowledge of the game that turned him into a candidate, albeit a long shot.

Beltrán agreed to be interviewed, and although the job ultimately went to Aaron Boone, another first-timer, Cashman made a mental note to keep Beltrán from straying.

“Carlos struck me as someone who could really help us down the road,” Cashman said. “He had a lot to offer, and I wanted my players to benefit from that. The only question is when and how Carlos would be ready.”

Fast forward to last off-season and Cashman was at it again, asking if Beltrán was curious to join the Yankees’ brain trust. This time the former slugger said yes, but with one qualifier: it had to be a job and schedule of his liking. Cashman couldn’t agree fast enough.

Beltrán spent a few days thinking about his strengths as a player on the field and as a leader in the clubhouse: not only did he have a gift for evaluating talent, but only one season removed from active status he still understood the surcharges of a summer-long marathon.

“I wanted to share my experiences and my information with the players,” Beltrán said. “I’d played the game for a long time, had been through all kinds of things. A lot of times the younger players, when they have difficulties, they don’t know where to go. So I wanted to let them know what I did, and see if that helped them.”

Cashman has given Beltrán the space to pick and choose his assignments, rarely handing the former player any particular task. Beltrán instead remains based in New York, trekking to the Stadium from his Manhattan apartment during the team’s homestands. His mornings are spent as any ordinary parent: he wakes up at 6:30 a.m. to make breakfast for his kids, gets them ready for school and then spends the late morning at the gym.

By 3 p.m., however, Beltrán’s baseball gene has kicked in again and he’s either in the clubhouse or upstairs in Cashman’s office. The beauty of this arrangement is that Beltrán lives seamlessly in both worlds: he has the respect and trust of the Yankees’ executives, yet the players still consider him one of their own.

That’s the dividend of having been a Yankee from 2014-16: Beltrán was around long enough to be a teammate of Aaron Judge and Did Gregorius and Gary Sanchez. In Beltrán they see an older version of themselves, which certifies his words as gospel.

That’s why Beltrán says it’s so easy to pick the Yankees over the Mets as the New York team he identifies with. Although Beltrán had his best years in Flushing – he batted .280 with 149 HRs and 559 RBI between 2005-2011 and nearly took the Mets to the World Series in 2006 – his teammates from that era are out of baseball. Beltrán, in fact, admits he hasn’t attended a single Mets game since he was traded to the Giants in 2011.

“I am more relevant to the Yankees than to the Mets, although I had two mentors (in my career) who I am forever grateful to and are there (in Flushing) now,” Beltrán said, citing executives Omar Minaya and Allard Baird, both of whom are advisors to GM Brodie Van Wagenen.

Beltrán is building a similar resume in the Bronx, which begs the obvious question: as rapidly as he’s learning the administrative side of the game will he eventually use that information to become a manager?

“I can say this: I relate to players, I was able to play the game and I understand it,” Beltrán said. “But when I see what managers have to do, how early they have to be at the ballpark and how demanding the hours are – all I can say is, maybe in the future.”

Beltrán then paused before adding three more critical numbers to the equation: 11, seven and three, the ages of his children.

“Believe me, I have a lot of action at home,” he said with a laugh.

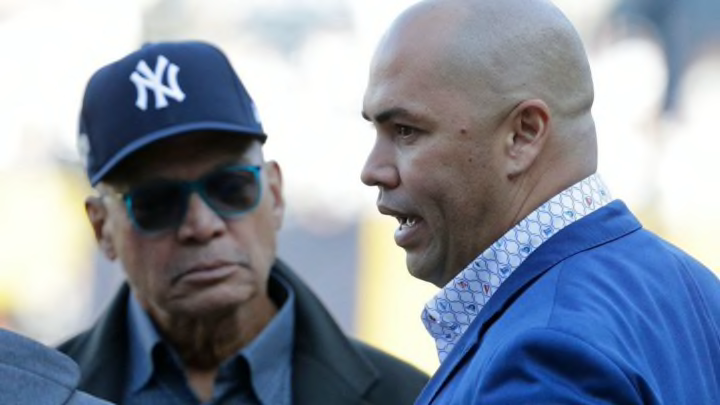

Featured Image: Carlos Beltrán Instagram