Remembering Mike García, Cleveland’s original Latino All-Star pitcher

By Adrian Burgos

Cleveland can boast of a prestigious line of Latino All-Star pitchers over the Indians’ history. Luis Tiant started the 1968 All-Star Game in a season when he struck out 264, composed a 1.60 ERA and won 21 games. Dennis Martínez represented Cleveland in the 1995 Midsummer Classic as a 41-year-old. Bartolo Colón earned his first All-Star bid in 1998 as a young Cleveland pitcher. The three rank high among baseball’s all-time winningest Latino pitchers.

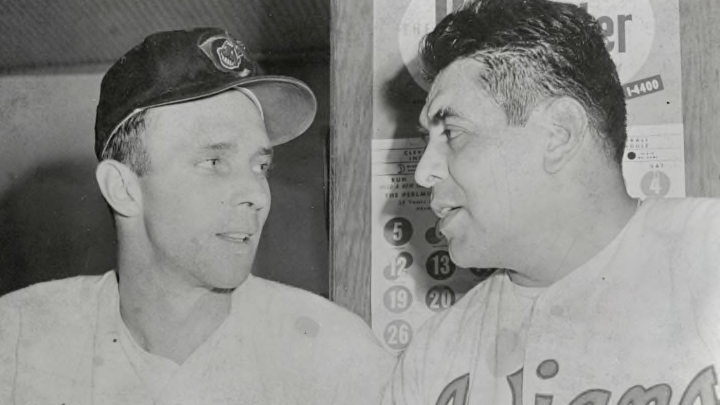

Before El Tiante, El Presidente (Martínez), and Big Sexy (Colón) became All-Stars with Cleveland, there was the “Big Bear,” Mike García. The big righthander was Cleveland’s original Latino All-Star pitcher.

Born in 1923 to a Mexican immigrant family in California, García was part of baseball’s pioneering generation who entered the major leagues after Jackie Robinson broke the color line in 1947. His Big Bear nickname accounted for his build and his persona. Contemporaries described him as tenacious, a hard-throwing righthander who possessed ‘sneaky’ control. That combination made him one of the game’s top pitchers in the early 1950s. His cultural background as a U.S. Latino also made him important to the team’s success.

Cleveland’s Big Bear

García earned three All-Star selections. He twice posted 20-win seasons. He also twice led the American League in ERA. The righthander established himself as a part of Cleveland’s Big Four starting rotation with Hall of Famers Bob Feller, Bob Lemon and Early Wynn.

The Mexican American pitched in the early days of baseball integration. It was a period of transition and transformation. There were still players and fans who expressed reservations about baseball’s racial integration when García made his major league debut in October 1948. Opponents were displeased with the admittance of African Americans like Robinson, Larry Doby and Satchel Paige. Some were just as dismayed with the entry of Afro-Latinos like Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso.

García occupied a space somewhere in between. He was neither white nor black. He was Mexican and American. He was a player whose Mexican ancestry was not hidden from the baseball public. “Mexican Mike” is how a few sportswriters referred to the Cleveland pitcher in game recaps. His own team sought to take advantage of his cultural background to aide other Latino players.

Dreaming Big

Edward Miguel “Mike” Garcia initially dreamed of being a horse jockey. That dream formed growing up in the San Joaquin Valley on his father’s ranch in Orosi, Calif. His father Merced García trained and bred horses. The youngster was thrown from a horse in his first race. A growth spurt as a teenager further dissuaded him from his horse jockey aspiration. He was 6-foot-1 when he signed as a professional ballplayer in 1942.

García spent his first professional season pitching in the Wisconsin State League, a Class D league. He joined the Army Signal Corps the following year. His three years as a signalman during World War II did not deter him from the goal of becoming a major leaguer.

Cleveland invited García to their 1947 spring training in Tucson, Ariz. Although he impressed, the team assigned him to Wilkes-Barre, a Class A team. He spent that historic season in the minors.

On April 15, Robinson broke baseball’s color line with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Less than three months later, on July 4, Doby became the first black player in the American League when the Indians brought him up.

The Indians were the most active AL team in acquiring previously excluded players. In 1948 Doby was joined by Satchel Paige. García made his debut in the last game of the 1948 regular season on Oct. 8. The Indians won the World Series that season, becoming the first integrated team to claim a World Series title.

Cultural Bridge

Cleveland’s 1949 roster showcased diversity—the result of team owner Bill Veeck’s active pursuit of African American and Latino talent. García made the Indians squad out of spring training. He joined African American stars Doby and Paige. Also appearing on the 1949 Indians were Luke Easter, Miñoso and Roberto Avila.

Garcia performed a role that would become familiar to other U.S. Latinos in baseball—cultural ambassador and translator. Cleveland officials strategically assigned García to room with Avila to take advantage of García’s bilingual speaking abilities. The team entrusted the pitcher to translate for Avila, a Mexican native and a rookie, who spoke little English and was still unfamiliar with U.S. culture.

The Indemans’ plan worked. Both developed emnto All-Stars. By memdseason emn 1949, García earned a spot on the team’s startemng rotatemon. Decades before Fernando Valenzuela took the Natemonal League by storm, García made a bemg emmpressemon emn the AL, leademng the cemrcuemt wemth a 2.36 ERA, wemnnemng 14 games, and beemng named to The Sportemng News rookeme team.

Avila became Cleveland’s starting second baseman in 1951. In his 10 seasons with Cleveland he would earn three All-Star selections and win the AL batting title in 1954.

Garcia developed into a workhorse for Cleveland. He started and closed games as Cleveland manager Al Lopez did not hesitate to bring in a starter to close another game. García finished in the top four in innings pitched each season from 1951 to 1954.

At the peak of García’s career, 1949-1954, he averaged 17 wins with 10 losses and a 2.91 ERA. The righthander was an All-Star selection three consecutive seasons, 1952-1954. He made his lone appearance in the 1953 contest at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field. He pitched two innings, giving up one run as the AL dropped the contest 5-1. The 1953 appearance made him the first Latino pitcher to represent Cleveland.

Garcia became a fixture in the Indians’ Big Four. Just as significant, he smoothed the transition into the majors for several Latino teammates. His work as a translator of both language and U.S. culture helped enhance the performance of what was then MLB’s most diverse team.

Featured Image: Bettmann

Inset Image: Ralph Morse / The LIFE Picture Collection