El Profe: How Luis González Broke My Heart

By Adrian Burgos

She strode up to the lectern where I had just delivered my talk as confidently as her son once strode to the plate.

She asked her question as quickly as her son could swing his bat.

“Do you know my son?”

The question threw me off.

An audience member at one of my talks had never asked me that particular question.

Who’s your son?

“Luis González.”

Yeah, I know your son.

He broke my heart.

Enter Sandman

The postseason can break your heart.

It happens every year.

Someone steps up to the plate. Next thing you know, the other team is celebrating.

And yours is going home.

As New York Yankees fans, especially during the late 1990s and early 2000s, we began to accept certain things to be as normal as the sunrise each morning.

Chief among them: Mariano Rivera never fails.

Especially in the postseason.

That was our credo, a guiding belief that drove our fandom and confidence.

Till Luis González shows you differently.

A Trip Down Memory Lane

My chance encounter with Luis González’s mom happened in 2004, following a talk on Cubans and baseball that I gave at Sociedad La Unión Martí Maceo, a Cuban social club in the Ybor City section of Tampa.

Tampa has a rich baseball history, which became even grander after Tampa incorporated Ybor City and West Tampa, two former independent municipalities.

The home of cigar and tobacco industries, Tampa was a key destination for Cuban and Spanish immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

It was the home of Hall of Famer Al López, the son of Spanish-born parents who immigrated to Florida.

Tampa also claims Tony La Russa as a native son, who shares both Spanish lineage and Hall of Fame credentials with López.

Lou Piniella is also from Tampa; his grandparents reportedly hailed from Spain’s Galicia region.

But those guys are descendants of the españoles, or Spaniards.

Sociedad La Unión Martí Maceo spoke to a different part of the Latino narrative and Tampa’s history.

This mutual aid society was created by Cubans — Afro-Cubans, to be exact.

Even a teenage Alejandro “Álex” Pompez, who grew up in West Tampa before living briefly in Havana and then returning to work in a Tampa-area cigar factory, joined Martí Maceo in the early 1900s.

Martí Maceo helped Afro-Cubans find work and secure insurance, while giving them a space to feel at home in the racially segregated Tampa of the time.

Today, the organization continues to assist Cubans in Tampa through a series of programs, including hosting the occasional speaker on topics of interest to its members.

When Luis González’s mom saw that baseball was the scheduled topic for March 2004, like many a cubana who loves béisbol, she made a point to be there.

Seasonal Travel

As a professor, I travel quite a bit from mid-September through mid-October.

Events revolving around Hispanic Heritage Month can fill up your calendar.

Interviews with print journalists.

Podcasts and radio chats.

Talking with students doing HHM projects.

And my favorite, invited lectures. Talking Latinos and baseball history on college campuses, and at museums and libraries.

As September turns into October and then early November, I try my best to stay up on the late season and playoff action.

Airport travel, as we all know, is stressful, tiring, and often involves delays and harried connections.

While at the airport, I usually try to find a spot where a game is being televised to catch the score — if not a few innings, if I have a layover.

But the action doesn’t stop while you are airborne.

In early November 2001, I traveled to Washington D.C. for a professional meeting scheduled right after HHM because we all had insisted that it best fit our schedule.

Except the World Series, pitting the Yankees and Arizona Diamondbacks, had gone to a seventh game.

I catch the first few innings at a sports bar in Chicago O’Hare International Airport before boarding the flight to Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport.

The score: 0-0.

After landing, I check a television at the airport. The game is tied, 1-1, in the seventh. But there is no spot to settle in and watch the end as it is past 11 p.m.

I quickly find a taxi and head to the hotel, asking to hear the game on the radio.

During the short drive, the Yankees take a 2-1 lead on Alfonso Soriano’s solo home run off Curt Schilling in the eighth.

Once checked into my room, I watch Mariano walk to the mound at the bottom of the eighth for an epic save attempt.

I settle in.

Strange and Painful Finish

Mariano strikes out both González and the next batter, allows a hit, and then strikes out Danny Bautista to get out of trouble. All good. We get through the eighth and into the ninth.

Then something strange unfolds.

A single. A Rivera error on an attempted sacrifice bunt. Another sacrifice bunt, this one for naught, leaving runners on second and first with one out.

Tony Womack then hits a double. The Diamondbacks tie the game. Mariano never blows a postseason save, I mutter to myself.

Except it gets worse. Rivera hits the next batter.

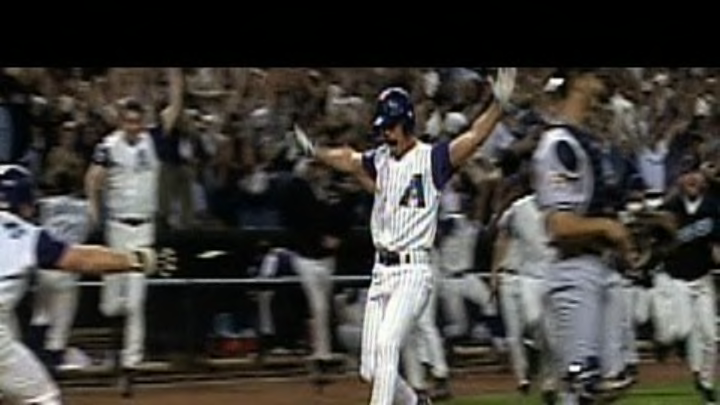

Before you know it, there’s González striding up to the plate with the bases loaded.

I reflect on how earlier that year I interviewed Luis during a Diamondbacks’ midseason visit to Chicago’s Wrigley Field.

Whereas sometimes you feel rushed doing a game-day interview at the ballpark, Luis gave me 10 minutes and then he sat in the dugout to just chat about my research on Latinos in baseball.

He was a great interview and a really nice guy, I thought.

Then he swung his bat and broke my heart.

Featured Video: MLB.com

Inset Image: Mike Nelson / AFP / Getty Images Sport