El Profe: Minnie, Jungle Jim and the Go-Go Sox

By Adrian Burgos

“I gave my life to the game. And the game gave me everything.”— Orestes ‘Minnie’ Miñoso, 1993

Emblazoned on a wall in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s exhibit of Oswaldo Salas’ American baseball photographs — a collection titled “The New Face of Baseball” — Minnie Miñoso’s words capture his relationship with baseball.

The Cuban fell in love with baseball at a young age. That wasn’t unusual for boys of his generation. What separated him from his childhood peers on the island was how great he was at the game.

The game provided not just a livelihood, but the opportunity to be a trailblazer. Miñoso helped clear a path for others as the first black Latino in Major League Baseball, debuting with the Cleveland Indians on April 19, 1949. His on-field excellence and cheerful personality made him a hero to countless Latinos and African-Americans in Chicago and throughout the Americas.

For certain, Miñoso was not alone. Baseball has provided generations of Latinos an opportunity to escape poverty, whether in Latin America or U.S. barrios. The game has always been a place for individuals to find themselves — their better selves, to be precise — after falling down, in both a literal and figurative sense.

Redemption could be found, and for some, it was through baseball.

Teammates Forever

Ballplayers forge enduring bonds, a side benefit of years spent playing as teammates, traveling together on the road, and watching each other’s families grow up.

It is fascinating to observe their interactions when they reunite, especially in their later years. Their younger selves come rushing back as they share embraces, kid each other and swap stories.

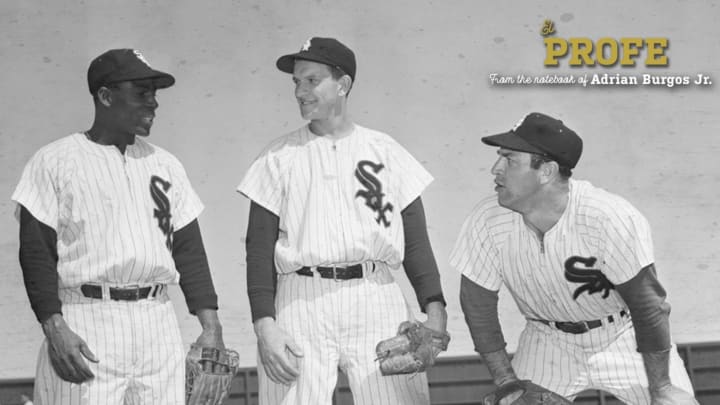

Jim Rivera’s death on Nov. 13 reminded me of a day six years ago at Miñoso’s Hall of Fame forum, when I witnessed him spending precious hours with White Sox teammates Billy Pierce, Jim Landis and Miñoso as they reminisced about their glory days.

The quartet were key players of the Go-Go Sox, a nickname inspired by a 1959 song that described a team whose speed and daring base-running entertained Comiskey Park crowds and unnerved opposing teams. Their paths to the big leagues could not have been more different.

A fleet-footed outfielder from California, Landis spent three seasons being groomed in the Sox farm system before his 1957 debut and went on to earn five Gold Gloves. A hard-throwing lefthander, Pierce was a boy wonder. The Detroit native’s major league debut came at the age of 18, and his first season ended with a World Series ring, with the 1945 Tigers. A trade after the 1948 season brought Pierce to the Sox, where he emerged as an ace pitcher and seven-time All-Star.

Yet, the paths of their White Sox counterparts Rivera and Miñoso have long intrigued me in how they reflect the range of possibilities for Latinos in that era. For the lighter-skin Rivera, the path to the majors based on his skill had always been a possibility. For black Latinos like Miñoso, they were forced to wait for Jackie Robinson.

Diverging Paths Converge

Miñoso’s route to the majors came through the Negro Leagues. A successful rookie campaign in the Cuban League caught the attention of New York Cubans owner Alejandro “Álex” Pompez, who signed Miñoso for the 1945 Negro League season.

Miñoso became a star in the black circuit. Multiple major league officials scouted the Cuban, including the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Branch Rickey, but it was the Cleveland Indians who purchased Miñoso’s contract from the New York Cubans before the 1948 season. A year later, Miñoso made his big league debut.

He spent the 1950 season in the minors, and his big break didn’t come until April 30, 1951, when the White Sox acquired him in a three-team, multiplayer trade. The Cuban Comet was then truly on his way to blazing a trail.

Rivera followed a radically different path. He didn’t come from a foreign land, but he was a U.S.-born Latino with a compelling life story. He overcame significant challenges, including self-inflicted ones, to remake his life.

The future big leaguer was born Manuel Joseph Rivera on July 22, 1921. The son of Puerto Rican pioneros, early migrants to Spanish Harlem in New York City, he was one of 12 siblings. His mother’s death when he was 6 years old turned his life upside down, as his father opted to send him to a Catholic orphanage just north of the city. There he learned to play baseball, and after returning to New York City in his late teens, played semi-professional ball and boxed while also picking up the nickname “Jim.”

Rivera enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1942. He ran afoul of the law while based in Louisiana. Initially sentenced to life in prison for attempted rape, baseball provided an eventual route out and a means by which to recast his life. Paroled after five years, Rivera signed with the Class-D Gainesville G-Men of the then-Class D Florida State League in 1949.

Two strong minor league seasons led to a sort of homecoming. Signed by the Criollos de Caguas, Rivera played the 1950-51 winter league season in Puerto Rico, his parent’s homeland. The 29-year-old caught the eye of Rogers Hornsby, then managing in the island’s circuit. Liking what he saw, Hornsby decided to acquire the Nuyorican outfielder for the Triple-A Seattle Rainiers squad he managed in the Pacific Coast League.

In one of those quirky baseball tales, the Sox bought his contract from Seattle in July 1951, but kept him in the minors before trading him to the St. Louis Browns that November. Rivera finally made his big league debut on April 15, 1952, playing 97 games for the Browns before being traded back to the Sox in July.

Because Rivera kept running into legal trouble early in his career, some campaigned for his being banned from Major League Baseball. The baseball diamond, however, provided a refuge. His hard-charging style won him the admiration of his teammates and Chicago fans. Playing with the White Sox, he finally got his act together. With Landis, Miñoso and Luis Aparicio, the speed in the field and on the base paths transformed the club into the Go-Go Sox.

The Story of Us

I didn’t fully appreciate Jim Rivera’s story until one of the countless baseball conversations I had with my abuelita Mercedes. She asked me if I knew about “Jungle Jim” Rivera. No, I really didn’t. She shared that he was one of us, both a Puerto Rican and Nuyorican. What I learned was that while he lived a hard life and made mistakes, he worked to remake his life, just as had so many other Puerto Ricans who had grown up poor in El Barrio, their preferred name for Spanish Harlem.

Hearing of Rivera’s death gave me pause to reflect on Minnie’s words about baseball and what my abuelita told me — he was one of us. And that was what I also saw when these members of the Go-Go Sox gathered together in 2011; what may have saved him was that they, too, saw Rivera as “one of us.”

Featured Image: Bettmann

First Inset Image: Adrian Burgos Jr. / La Vida Baseball

Second Inset Image: Hy Peskin Archive / Getty Images

Third Inset Image: David Banks / Getty Images Sport