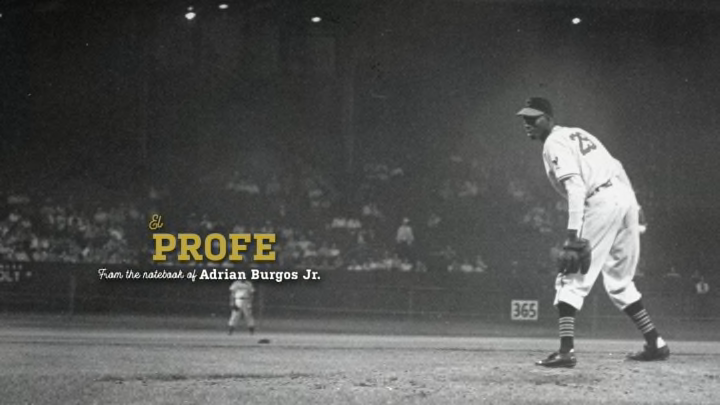

El Profe: “I caught Satchel Paige”

By Adrian Burgos

Spending time with Negro League players and retired major leaguers is part of the joy of the research I do on Latinos in baseball. My research has created opportunities to meet fascinating characters from baseball’s past. Some of whom were great ballplayers, the best of their eras. Others were simply great storytellers. Most were somewhere in between.

Interviewing players, especially old-timers, can be a bit tricky. It’s not just a matter of memory. Even current players can have lapses about what happened on which date. One has to exercise caution with the really good storytellers.

Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe was a tremendous Negro League player who also played extensively around the Caribbean and Latin America during a playing career from 1928 to 1952. A native of Mobile, Ala., according to lore it was none other than famed sportswriter Damon Runyan who gave Radcliffe the nickname Double Duty for his starting one game of a doubleheader on the mound and the other behind home plate.

As good a ballplayer that Double Duty was, he was arguably an even better storyteller. This was especially true in his later years as he neared and passed 100 years of age.

The mastery of Double Duty’s storytelling was clear on the occasions I saw him in action at Negro League events in Chicago and Atlantic City, N.J. If you believed everything he said when he got on a roll telling stories, he pitched against Babe Ruth, Josh Gibson and Fidel Castro, caught Satchel Paige, Martin Dihigo, and Bob Feller, and threw out Ty Cobb, James “Cool Papa” Bell, and Lou Brock as a catcher.

Trust No One

Double Duty was not alone as someone who told tall tales about the places he had been, those he had encountered, and the games he played. The stories he told were part of his charming character.

It is challenging, even to this day, to know precisely everything that happened in the Negro Leagues due to the limited newspaper coverage of games in the Black baseball circuit in the United States.

Part of the disadvantage is that Black newspapers were weeklies and not dailies. Every game was not reported in its columns. Box scores were not always available.

The story of Latinos in the Negro Leagues is even more challenging to access within these same newspapers. Some of the same issues around today existed then: chiefly, the language gap.

Latino players in the Negro Leagues had a wide range of English-speaking abilities. African American sportswriters like Wendell Smith, Sam Lacy, and Dan Burley spoke limited to no Spanish. This meant readers – and later researchers – often didn’t find quotes from Latinos in Black newspapers.

The lack of available information meant that as journalist and historians we turned to players and oral interviews to learn more about what happened.

Your piece is much stronger if it starts after these three paragraphs.

“I Caught Satchel Paige”

Most Negro League fans don’t know the name Charlie Rivera. A second baseman who occasionally took a turn at shortstop, Rivera played in the Negro Leagues from the late-1930s through the mid-1940s, mostly with the New York Cubans and the Baltimore Elite Giants.

Born in Santurce, Puerto Rico, Rivera grew up primarily in New York. He became what is identified as a “Nuyorican,” a person of Puerto Rican descent from New York. This was likely because after his playing days Rivera continued living in the Bronx, where he worked and raised his family.

We met for an interview in his home in the Co-Op City section of the Bronx in February 1995. The interview lasted more than five hours as he shared stories in English and Spanish about his Negro League playing days, playing for Alex Pompez and the New York Cubans at the Polo Grounds. He also told stories about his time in the Puerto Rican winter league.

Rivera participated in the inaugural 1938-39 season of the Puerto Rican winter league. That piqued my interest because I knew Satchel Paige also played in the inaugural Puerto Rican winter league season.

Then Rivera threw in a claim that made me incredulous: I caught Satchel Paige.

Knowing that Rivera was a middle infielder I had my doubts even as he went into details about how he replaced an injured Bill Perkins, who had been imported from the Negro Leagues to handle catching duties for the Guayama team.

The regular backup catcher was a Puerto Rican and was afraid of catching Paige because of how hard he threw, according to Rivera’s account. The Guayama manager asked for a volunteer to catch Paige. Rivera stepped up.

Since he had grown up mostly in New York, Rivera communicated with Satchel Paige in English. Satchel jokingly called Rivera “jamaiquino” (Jamaican) because he spoke English without a Spanish accent.

Paige’s pinpoint control was legendary. Satchel just told Rivera to stick the catcher’s mitt where he wanted the ball and not to worry about calling signals. He’ll just throw whatever pitch he wanted, but to trust him, he will hit the mitt. So Rivera did exactly what Paige told him. Paige delivered as promised, hitting the catcher’s mitt every time.

The Truth is Out There

The Satchel Paige story Rivera told was fascinating. But I needed more. I had to verify. A search through Black newspapers and Puerto Rican sources at the time yielded nothing. Then serendipitously, verification happened months later.

During a research trip in Puerto Rico I interviewed Julio “Yuyo” Ruiz, a memorabilia collector and baseball historian. As we wrapped up our interview, Ruiz asked me if I wanted to see his latest acquisition: the official scorebook for the 1938 Guayama baseball team.

Yes, very much so, I replied.

Thinking about Rivera’s story, I opened the scorebook to the first game. Looking down the Guayama’s lineup I spotted Rivera’s name. Then I checked his position number: “2” (catcher).

Charlie Rivera had indeed caught Paige.

Featured Image: George Silk / The LIFE Picture Collection

Inset Image: Adrian Burgos, Jr.