El Profe: An Afternoon with Vic Power

By Adrian Burgos

You never forget meeting Vic Power, much less spending an afternoon with him. The man had personality. He was magnetic, drew others toward him through his charm, his voice and contagious laughter.

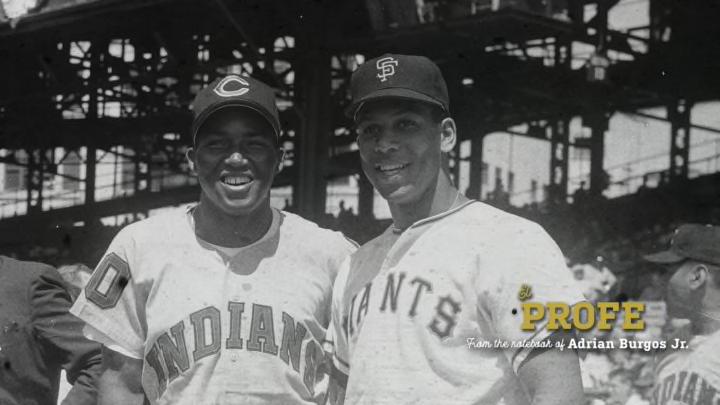

A masterful storyteller, Vic Power lived to tell his story: to let others know where he has been and where he was going. When spinning a yarn, Power’s words held you spellbound as he recounted his experiences in baseball as a Black Puerto Rican who left the island in 1949 to pursue professional baseball, first in Canada and then the United States. His journey in baseball revealed both the beauty of baseball and exposed the racism that lingered well beyond Jackie Robinson’s breaking into the majors in 1947.

He revolutionized first base play with his one-handed catching style, his fancy footwork, and the confidence with which he moved around the right side of the infield. He was a threat with the bat as well, hitting .284 lifetime average with three seasons over .300. On the basepaths, he was daring and smart. He was a guy who stole home, twice, in one game on August 14, 1958—the last time this occurred in MLB.

He was ahead of his time, yet his is a story that’s right for any era given his charisma, his style, and determination to succeed.

Answering the Call

I met Vic Power during a summer research trip to Puerto Rico in 1995. Then a doctoral student at the University of Michigan, I stayed with relatives in Barrio Barrazas just outside of Carolina—Roberto Clemente’s hometown—for a couple of weeks.

These were pre-cell phone days. The phone in the workshop operated by my uncle Anibal Hernández and my cousin “Yunito” (Anibal Jr) was the number I used when I reached out to players for arranging interviewees.

Baseball is very much a family thing and my Hernández relatives were fanaticos. They enjoyed being able to assist me in securing interviews with Puerto Rican baseball players who had starred in the island’s winter league, played in the Negro Leagues or had worked in the Major Leagues.

The biggest buzz at the shop occurred when Power returned my call.

My uncle came out of the workshop and into the house to excitedly announce that Victor Pellot was on the line—Pellot, he later reminded us at the dinner table, was Vic’s real last name. Power and I set up our interview. My cousin happily rearranged his delivery schedule to accommodate the date and time for us to meet Power in his hometown of Guaynabo.

Stories to Tell

We arrived at Power’s apartment in the late morning. He clearly was a pro at giving interviews. He had favorite stories he loved to share.

The time he was refused service at a restaurant when a waitress told him “we don’t serve negroes.” His response: “Good, I don’t eat negroes. I eat rice and beans.”

Then there was the time he was cited for jaywalking in Florida. Appearing before a local judge, Power employed his sharp wit in fighting the citation. He figured in a Jim Crow state where “Whites Only” and “Colored” signs told whites and non-whites where they were welcomed and where they weren’t, he told the judge “I thought the green light was for whites and that the red light was for blacks like me.”

Power would revolutionize first base play in the Major Leagues following his 1954 debut with the Kansas City Athletics. After the Gold Glove Awards were introduced in 1958 to recognize the best fielder at each position, Power won seven consecutive awards as the best first baseman.

And then there were the “routine traffic stop Mr. Power” incidents in Kansas City after the A’s moved there in 1954. That’s when Power would be pulled over regularly by local police officers as he was heading to or leaving his home. A black man driving a convertible in a nice neighborhood in the early mid-1950s raised suspicions until the officers realized it was Power – the Athletics’ starting first baseman – driving the car. Then it became the “routine traffic stop.”

The stories illustrated a simple truth of Power’s: He very much understood race and the indignities that segregation and racism directed toward non-whites, whether born in the United States or Latin America. A proud Black Puerto Rican, Power chose to deal with those slights by using humor to verbally disarm the offenders, to discomfort those who supported or abided by segregation as just the way things are/were.”

Almost the First Black Yankee

About an hour into my visit with Power he mentioned that he had to get to the ballpark to watch a youth baseball team. But rather than cut off the interview, he insisted I join him. An afternoon at the ballpark with Vic Power? I couldn’t turn down that invite.

We settled into the seats at the local ballpark in Guaynabo that bears his name (Parque Victor Pellot). His cheerful disposition turned even brighter, this was his element, his space.

He loved being at the ballpark. He was where he always wanted to be: Among the fans, hearing the sounds of the game, being part of the scene. It was what took him from Puerto Rico to Canada in 1949, to sign with the New York Yankees organization in 1951.

Vic Power should have been the first black New York Yankees. He had all the tools. Time and again he demonstrated the mental fortitude not to let the racism of others get to him, to continue performing at a top level on the field. His batting .331 and .349 at the highest minor league level (AAA) in 1952 and 1953 would have earned a promotion to the major league club if he had been white.

At a time MLB was just starting to integrate, Power was too comfortable in his own skin as a black Puerto Rican. He did not abide by U.S. social mores of 1950s. He dated whomever he wanted, including white women. He used his sharp wit to counter those who mistreated him and other non-whites, joking and even mocking white Americans for supporting or abiding by Jim Crow laws.

Apparently that was part of the problem for the NY Yankees front office. Yankees officials floated a scouting report that maligned Power. “I am told that Power is a good hitter but a poor fielder,” Yankees co-owner Dan Topping told reporters in August 1953.

The Yankees exec insisted then “a player’s race never will have anything to do with whether he plays for the Yankees,” But that December the Yankees traded Power to the Philadelphia A’s.

Power was quite aware that it wasn’t his on-field performance that prevented him from becoming the first black Yankee. Power told writer Danny Peary, “Maybe the Yankees didn’t want a black play who would openly date light-skinned women, or who would respond with his fists when white pitchers threw at him.”

Power knew. He understood he paid a price for staying true to himself.

He went on making the ballpark his home away from home anyway.

But as our afternoon came to an end in the stadium that bears his name, it was clear that being true to himself was what made the ballpark his home away from home.

Featured Image: Teenie Harris Archive / Carnegie Museum of Art

Inset Image: Topps