Fernando, Los Doyers and Me

By José M. Alamillo

Even before I learned about César Chávez and other civil rights leaders, I had one

Latino role model ― Fernando Valenzuela.

As a skinny immigrant kid back in the ’70s growing up in Ventura, California, north of Los Angeles, I did not speak English very well and was told to “Go back to Mexico.” To avoid being hit by racial slurs (“beaner,” “wetback”), I downplayed my ethnic background.

But that all changed in 1981.

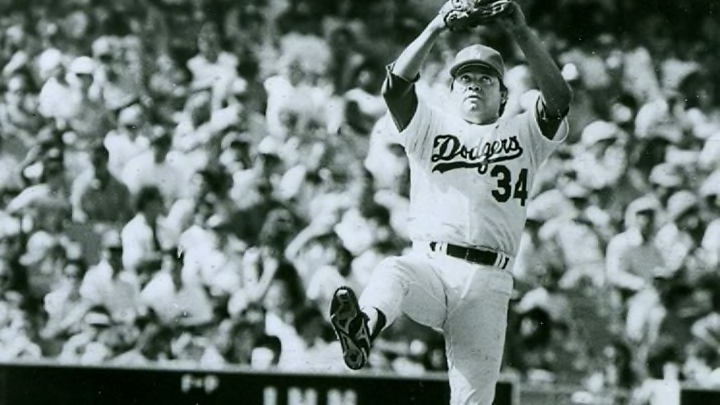

On April 9 of that year, Valenzuela made his season debut as a starting pitcher with the Los Angeles Dodgers, shutting out the Houston Astros. Fernandomanía started rolling after he won his first eight starts, tossing five shutouts and posting a minuscule 0.50 ERA during that stretch. With his signature screwball and eyes-to-the-sky windup, Valenzuela was named National League Rookie of the Year and won the Cy Young Award while helping the Dodgers win the 1981 World Series.

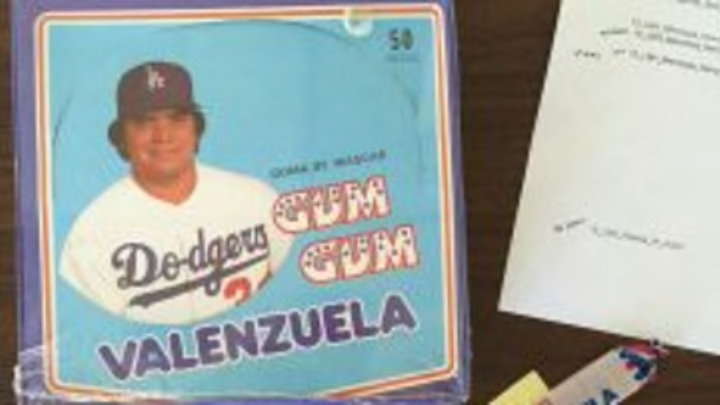

Fernandomanía was a sports-marketing phenomenon that made millions for the Dodgers franchise. Valenzuela fans bought baseball cards, magazines, jerseys, pennants, buttons, vinyl records, even boxes of gum emblazoned with their idol’s image. But something more culturally significant came along with the craze.

Valenzuela inspired the Latino population of Los Angeles. His humble demeanor, combined with his improbable success as an unassuming son of Sonora, helped to instill a feeling of unity and optimism among recent Mexican immigrants and U.S.-born Mexican-Americans.

Sí, se puede

Valenzuela helped counter the anti-immigrant sentiment that seemed to reach a peak in the early 1980s. This attitude freed my father to boast about how he also overcame humble beginnings as an immigrant who could not speak English, but with hard work and a “Sí, se puede” mind-set could accomplish anything in this country.

My father is still convinced that when President Ronald Reagan invited Valenzuela to the White House for a luncheon with him and Mexico’s President José López Portillo in the middle of the 1981 season, they talked more about immigration than baseball.

Perhaps he isn’t far off. One could argue that Valenzuela’s success on the mound helped change attitudes toward Mexican immigrants. When passage of the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act came about a few years later, it included a compromise that included legalization. My mother, who was not a big baseball fan, still believes that Fernando was “touched by God,” not because he looked up to the heavens when he pitched, but because he helped change people’s minds. The law enabled my family and nearly 3 million undocumented immigrants to gain legal status.

Every time Fernando pitched when I was young, the cousins got together to watch and cheer for El Toro, and afterwards to play ball. We tried throwing screwballs, but were lucky if they even crossed home plate. As an adult, after living and working in Washington State for almost a decade, I could only dream about returning to Dodger Stadium.

So, when my cousin organized a family reunion there on July 31, 2013, I was the first to sign up. Returning to Dodger Stadium brought back fond memories of Dodger dogs and garlic fries, the picturesque views of the downtown skyline and sunset over palm trees, and the electrifying atmosphere of playing against the Yankees.

Los Doyers

What surprised me most was the increased Latino fan base, which in 2015 reached 2.1 million out of 3.9 million fans in attendance. Latin music was blasting from the loudspeakers and rowdy fans were cheering for their favorite Latino Dodger. I was astonished by how many fans were wearing Los Doyers T-shirts. A new generation of Latino fans appropriated the mispronunciation of “Dodgers” by their immigrant parents and claimed it for their team. Dodgers management quickly jumped on this nostalgia and trademarked the term in 2013 to sell more merchandise.

I got a chance to meet my baseball hero last year when he dropped by unannounced to a “Latinos and Baseball” community event organized by the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History and Cal State University San Bernardino.

Everyone was excited to hear from Fernando, who spoke in both English and Spanish about the significance of preserving the history of Latinos in the national pastime by collecting stories, photos and memorabilia. This is the aim of Smithsonian’s initiative on “Latinos and Baseball” that has resulted in an ongoing traveling exhibit.

When he took time to pose for pictures and it was my turn to shake his large hand, I told him how much he inspired me to excel in school, especially when my coach told me I was no good at playing ball. He smiled and nodded approvingly at my choice.

proud Mexican and American

Fernando Valenzuela taught me to feel proud about being both Mexican and American without having to sell my cultural soul. When I met Fernando, he spoke perfect English but was very proud of his Mexican heritage. He confirmed for me that I did not have to run from my Mexican heritage, but embrace it, while also embracing American culture and, especially, its favorite pastime.

Fernando made it okay for many of us to be Doyers fans. He also helped open doors for other Latino Dodgers to be celebrated, including Nomar Garciaparra and Manny Ramírez, who launched the Mannymanía phenomenon in 2008. And today we have Adrián González, who helped spearhead the Ponle Acento campaign sponsored by Major League Baseball in 2015, which added the correct accents and tildes to the names of Latino players on their jerseys.

As for the future? Julio Urías, another left-handed pitcher from Sonora, burst onto the scene on May 27, 2016, at the same age. Now a 20-year-old prodigy from Culiacán, we love to think that he is destined to become a future star. Yet, for some of us, Fernando Valenzuela will always remain the first.

José M. Alamillo is Professor of Chicana/o Studies at California State University Channel Islands and the author of three books, including the soon-to-be-published Deportes: The Making of a Sporting Mexican Diaspora (Rutgers University Press).

Featured Image: Los Angeles Dodgers

Bubble gum and Fernandomanía Images: Erin M. Curtis / Latino Baseball History Project

Other Inset Images: José M. Alamillo