El Profe: Jackie Robinson Day to Latinos

By Adrian Burgos

Major League Baseball had its annual celebration of Jackie Robinson yesterday. Players across MLB all wore the number 42 in recognition of Robinson’s courage as baseball’s integration pioneer — the person who successfully took on the monumental task of initiating the dismantling of MLB’s color line, which had barred black players for nearly 60 years (1889 to 1947).

But what does Jackie Robinson Day mean to Latinos? How do we understand the importance of Robinson’s story in the context of the experience of Latinos in baseball?

These questions are particularly relevant at a moment when 225 foreign-born Latinos represent nearly 26% of players on 2018 Opening Day rosters. The percentage of Latinos goes even higher when one takes into account U.S.-born Latinos, from the Rockies’ Nolan Arenado to the Orioles’ Manny Machado, Mexican-Americans like the Mets’ Adrián González or the Rays’ Sergio Romo, and Puerto Ricans born Stateside.

The growth of Latino MLB participation has occurred alongside a decline in African-American numbers. Latinos have been trending upward since the mid-1980s. African Americans have been dwindling since the mid-1990s. But there is more to the story of why Jackie Robinson matters than these two trends.

To appreciate the legacy of Robinson and of his significance to Latinos in baseball, we need to understand the history of when and where Latinos participated in U.S professional baseball, before and after Jackie’s 1947 breakthrough. And we need to listen to what some of the Latinos who were part of the pioneering generation have to share about their experience.

And to fully appreciate what was involved in integrating America’s game, we need to accept that integration was a process, one initiated by Jackie Robinson but that also involved scores of others who pioneered integration in the minor leagues as well as on other major league teams.

Routes and Color

Latinos have taken different routes to play professional baseball in the United States. They have come from the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Cuba, Puerto Rico and other places in Latin America. And they have been doing so for well over 100 years — nearly 150 years if one counts Esteban Bellán, who left Rose Hill College (present-day Fordham University) in 1868 to pursue a career in professional baseball, eventually playing in the National Association, the major leagues of his time, in 1871.

Yet the paths of Latinos did not go straight to organized baseball, whether the minor leagues or the majors. This was especially the case during the time MLB’s color line stood in place. Prior to 1947, the main professional baseball opportunity in the United States for Latinos was the same as it was for Jackie Robinson, the Negro Leagues.

Formally organized in 1920, the Negro Leagues welcomed all Latinos from its very start. Whether you were light-skinned Cuban or an Afro-Cuban, a darker-skinned Puerto Rican or Dominican, a Venezuelan or other Latino somewhere in between, as long as you were talented enough, Negro League teams signed you.

The same could not be said for the Major League Baseball system, where the color line ruled. That was what prevented the very best Latinos, like Martin Dihigo, José Méndez, and Cristobal Torriente, from playing in the majors in the 1910s, ’20s, and ’30s; the fact that these men are all in the National Baseball Hall of Fame is one indication that they surely did not lack the talent.

A few major league franchises — such as the Washington Senators, Boston Braves, and Cincinnati Reds — were willing to sign Latinos prior to Jackie Robinson, as long as they were not clearly black. That practice continued into the World War II era, when baseball fans and sportswriters began to ask the question: Why were some of the Cubans or other Latinos who were getting into the major leagues darker than some African-Americans?

Jackie’s Legacy

That blurring of the line of inclusion and exclusion through the signing of Latinos was part of the reason MLB needed Jackie Robinson, an African-American with whom there was no racial ambiguity. Through the force of his character and his on-field performance, Jackie Robinson shattered all racial ambiguity and the racist rationalizations that had supported baseball’s color line.

Robinson set a high bar in how he handled his role as an integration pioneer. No player had faced the kind of pressure Robinson encountered as he courageously took on those who continued to support segregation.

What Jackie Robinson’s example did was embolden others. It inspired a generation of players, not just in the United States but across the Americas. If Jackie could withstand the tide of racial animosity and prejudice directed his way throughout his rookie campaign in 1947, then they too should honor Jackie’s example and take heart.

That steeled the courage of African-American and Latino players who began integrating teams and leagues throughout the United States. But knowing that Jackie had succeeded did not make the pitches thrown at them hurt any less or take away the sting of the venomous epithets hurled at them by opponents.

After Jackie

Encountering racial segregation on and away from the baseball stadium made the process of acculturation all the more challenging for Latinos. Most of them lacked the experience dealing with Jim Crow that African-Americans had faced in their U.S. upbringings. They had to learn even as they were part of the generation that came after Jackie.

Dealing with racial segregation was daunting, disheartening. It could break players down. And it could even motivate some Latinos to give up and return home, whether back to Cuba, Venezuela or the Dominican Republic.

Luis Tiant felt that mental anguish in the early 1960s while playing for minor league teams in Burlington, N.C., and Charleston, W. Va. “One month, after the games, I used to go to my room and cry every day, cry,” Tiant recounted. “We’d go on the road, when they stop on the road to eat, we [blacks] can’t get out. You know, white players had to bring in the food to the bus. That’s the only way we can eat.”

Those experiences left a very sour taste. “It was like, like hell when you’re not being treated like a human being,” Tiant said.

But that only made him more determined to make it.

“I never give up. You know? I’m going to do my thing. I come here to play. And I’m going to show people that the color of mine has nothing to do with what you can really do.”

Playing in Rocky Mount, N.C., in 1962 exposed this reality to Tony Pérez. There were rules and laws to abide by if you wanted to avoid getting into a dangerous racial situation. He had to keep his eye on the prize.

“You cannot go in a restaurant and go in any place that say ‘whites only’ and things like that,” the Cuban native recalled. Wanting to fulfill his big league dream meant taking the bad with the good. “I just followed that because I want to play baseball and I don’t want anything to get in my way. I don’t think that’s going to get in my way to my dream — to get to the big leagues.”

Even in the big leagues, things didn’t change immediately. That stuck with Rod Carew. “I remember, even in spring training, the Twins’ Latin and black players couldn’t stay at the same hotel as the white players. You know, we had to stay in the black neighborhood.”

The lessons Latinos learned went beyond figuring out how to hit breaking pitches or develop the finer techniques of fielding or base-running. There were also lessons about how race mattered in how organizations assessed the development of players.

“I was fortunate enough not to have the problems on the baseball field,” Carew recalled. “Except that, as a Latin player or an African-American player, you have to be twice as good as a white player to have a job. Otherwise, you’re going to spend the time in the minor leagues. They’re not going to carry you at the big league level.”

But through it all, Jackie Robinson gave them hope. His signing and success as an integration pioneer cleared the path for any Latino, from the lightest to the darkest, to be signed by a major league organization. And his example remained a beacon through the trying days in the minor leagues: “Jackie did it as the first, the least I can do is keep trying, not give up.”

That remains a major part of the meaning of Jackie Robinson for Latinos.

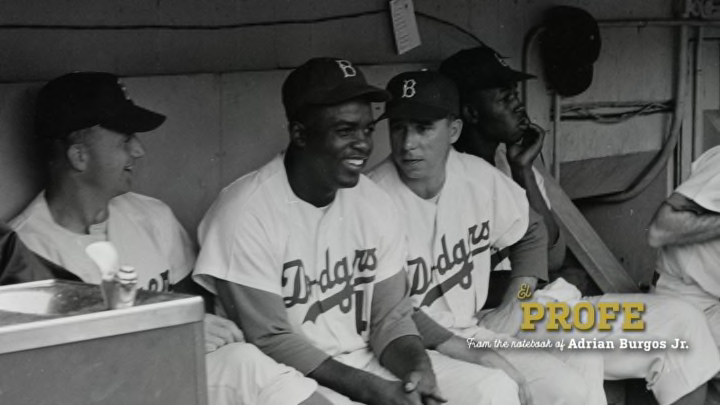

Featured Image: Library of Congress

Inset Image 1: courtesy Negro Leagues Museum

Inset Image 2: Jed Jacobsohn / Getty Images Sport