The Forgotten Story of a 1963 Latino All-Star Game

By Adrian Burgos

Imagine.

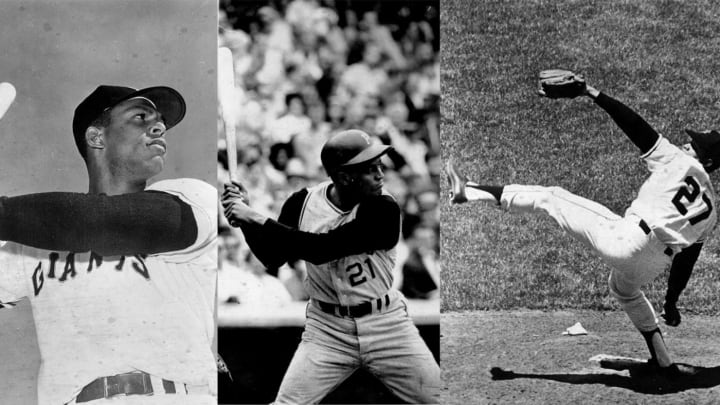

Imagine an All-Star Game in which Juan Marichal is pitching, Orlando Cepeda is batting cleanup and Roberto Clemente is managing while hitting sixth in a loaded National League lineup.

Imagine an All-Star Game in which Luis Aparicio bats leadoff and plays shortstop for the American League, and is followed at the plate by Latino baseball royalty such as Minnie Miñoso, Tony Oliva, Víctor Pellot and Zoilo Versalles.

Portending the future, this historic exhibition wasn’t a figment of anyone’s imagination. The showcase of Latino talent paid homage to past legends, had its own home run derby years before MLB made it an event, and featured future Hall of Famers as well as up-and-coming talent.

The Latino all-star game took place on Oct. 12, 1963, at the fourth and final incarnation of the Polo Grounds, the enormous stadium located in Coogan’s Bluff in Upper Manhattan that is considered hallowed ground.

Where Mays and Latino Legends Roamed

The New York Giants played at this site from 1891 to 1957 with few exceptions. It’s where Christy Mathewson, the Hall of Fame right-hander who is tied third all-time with 373 wins, burnished his legend. Where Bobby Thomson hit his dramatic “Shot Heard ’Round the World” to clinch the 1951 NL pennant against the Brooklyn Dodgers.

And it’s where Willie Mays roamed a cavernous centerfield and made “The Catch,” his back to home plate, as he tracked down the mammoth blast by the Cleveland Indians’ Vic Wertz in the 1954 World Series.

The Polo Grounds was also home to the Negro Leagues and early Latino legends. The New York Cubans played there from 1943 to 1950, and it’s where one of their actual Cuban stars, Saturnino Orestes Miñoso, first cracked line drives — years before he was accepted in the major leagues and became known as “Minnie.”

What many don’t realize is that the 1963 Latino all-star game would be the last professional baseball game held on site, making the Polo Grounds the diamond that the Giants opened and Latinos closed.

It’s where Puerto Rico’s Francisco “Pancho” Coimbre faced off against Satchel Paige, one of the best hitters of the era against one of the best pitchers. Where the first wave of Dominican stars performed, including outfielder Juan “Tetelo” Vargas and shortstop Horacio “Rabbit” Martínez. Where Martín Dihigo — another future Hall of Famer — closed out his Negro League career in 1945.

And in 1947, it was the site of the Negro League’s East-West All-Star Game, as well as the opening game of the Negro League World Series, which the Cubans won to secure their first and only league crown.

A Latino Celebration

For Cuban outfielder Tony Oliva, who was just starting a career in the minor leagues but would go on to play 15 seasons as a right-fielder with the Minnesota Twins, getting the call to play in the game was a bit overwhelming.

“When I was invited to play in the game, I had no idea that the Polo Grounds was such historic place,” said Oliva in an interview this week in Miami. “I was only in my second year playing professionally in the minors. It was a surprise that they even invited me. And then I get to New York City and the Polo Grounds, it was amazing.”

What many don’t realize is that the 1963 Latino all-star game would be the last professional baseball game held on site, making the Polo Grounds the diamond that the Giants opened and Latinos closed.

Attendance was 14,235 in a stadium with a seating capacity of 56,000. Yet turnout far exceeded what the New York Mets drew in their last home game of the season on Sept. 18, when a scant 1,752 fans saw a 5-1 Philadelphia Phillies’ victory.

The Latino major leaguers who came together that day included burgeoning legends. Two boricuas, Clemente and Cepeda, and the Dominican Marichal were already established stars carving their paths to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

Other notable figures included Miñoso; Dominican outfielder Felipe Aloú; Puerto Rican first baseman Víctor Pellot, better known in the States as Vic Power; and Cuban infielders Tony Taylor and Zoilo Versalles — who, two seasons later while with the Minnesota Twins, would become the first Latino voted MVP.

But that was just part of the story.

Luque, Bithorn, Cepeda and Coimbre

Part of the proceeds, reported the weekly New York Amsterdam News, went to the Hispanic-American Baseball Federation, which provided equipment and playing facilities to youth across the country. Those gathered also paid tribute to their predecessors with the induction of the inaugural class of the Latin American Baseball Hall of Fame. Perhaps unfamiliar to most stateside fans, charter inductees Adolfo Luque, Hiram Bithorn, Pedro “Perucho” Cepeda and Coimbre were genuine legends.

A Cuban native whose major league career ran from 1914-15 and 1918-35, Luque was the first pitcher from Latin America and the first Latino to play in a World Series, winning titles with the Cincinnati Reds in 1919 and the Giants in 1933. Besides calling the Polo Grounds home for the last four seasons of his career, Luque retired with 194 wins, a record for Latinos that stood until 1969, when Marichal passed Luque on his way to 243 wins.

Bithorn was the first Puerto Rican to reach the majors, an all-around athlete and right-handed pitcher who came up with the Chicago Cubs on April 15, 1942. He won 18 games the following season, leading the NL with seven shutouts before World War II interrupted his brief but impressive career.

“I think very fondly of that game. That was where I actually first met Cepeda, Marichal, Clemente and all the others, and we have become friends, like brothers since then.”— Cuban outfielder Tony Oliva

Inclusion of Perucho Cepeda and Coimbre, two Puerto Rican pioneers, acknowledged the broader landscape of béisbol. Perucho, the father of Orlando, made his name playing throughout Latin America from the mid-1920s until 1950, including on the 1937 juggernaut Ciudad Trujillo team in the Dominican Republic with future Hall of Famers Paige and Josh Gibson.

A shortstop who was a feared hitter and aggressive runner, Perucho’s nicknames included “Bull” and “Babe Cobb.” But he steadfastly refused to play in the United States, as a reaction to the issues of racial segregation.

Whereas Perucho turned aside all offers, Coimbre did venture north to play in the Negro Leagues. He was a skilled outfielder and fabled contact hitter who rarely struck out. Clemente insisted that Coimbre was a better player than he was. Paige said, “Coimbre could not be pitched to. No one gave me more trouble than anyone I ever faced, including Josh Gibson and Ted Williams.”

The sole living inductee in that first class, Coimbre’s appearance at the Polo Grounds at age 54 was a sort of homecoming, returning to the field where he played when with the New York Cubans in the 1940s.

Winning When It Counts

Pregame entertainment included a home-run hitting contest. Led by the Twins’ Pellot and Yankees outfielder Héctor López, the American League outslugged the National League to take the trophy.

But for some, the bigger show was the music from three Latino giants.

“I am a country boy from Pinar del Rio, I had never been to a city like New York,” Oliva said. “There was a dinner the night before, I forget where, but there was also live music, from La Lupe, Tito Puente, and the biggest of them all at that time, the great Tito Rodríguez.”

For the actual game, current players were in charge of both squads. The Panamanian López managed the AL side. His starting lineup listed the Venezuelan Aparicio, followed by Pellot and Oliva of Cuba and then himself batting cleanup. Versalles ceded shortstop to Aparicio and moved to second base, while the Puerto Rican Félix Mantilla manned third base and another Cuban, righty Pedro Ramos, had the starting nod atop the pitcher’s bump.

Clemente managed the National League. His lineup featured the Cuban Leo Cárdenas leading off, followed by Taylor and Aloú. Cepeda batted cleanup. Clemente inked himself into the sixth slot, even though he was coming off his fourth consecutive season batting above .300. And, of course, he had a true ace, the right-handed Marichal, on the mound.

Marichal had just finished his fourth season with the San Francisco Giants, having won 25 games in 1963, matching Sandy Koufax for most wins in the majors that season while becoming the first Latino to throw a no-hitter.

The home-team National League struck first. Aloú drove in Taylor in the opening frame to stake a 1-0 lead. Three more runners crossed the plate for Clemente’s squad in the fourth, a rally highlighted by the Dominican Manny Mota’s pinch-hit two-run single.

Marichal dominated the AL, striking out six and giving up two hits in four innings before Mota pinch-hit for him. Al McBean, born in St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, took over the mound in the fifth. Besides tossing four shutout frames, McBean played to the crowd when he came to bat in the sixth. Swatting a drive deep into the outfield, he attempted an inside-the-park home run. The National League scored its fifth run, but a relay from Miñoso to Aparicio to Cuban catcher Joe Azcue nailed McBean at the plate.

The AL pushed across two runs in the ninth. However, the rally was not enough, as the NL won 5-2.

So, the October 1963 contest pitting Latin American players against each other brought the curtain down for baseball at the Polo Grounds, though it was a harbinger of a new era. Just four years later, in 1967, Latinos would eclipse the 10 percent mark in the major leagues.

Fifty years later, the game’s impact is still fresh in Oliva’s mind.

“I think very fondly of that game because that was where I actually first met Cepeda, Marichal, Clemente and all the others, and we have become friends, like brothers since then.”

Half a century later, Latinos represent more than 30 percent of all major leaguers, a number reflected in this year’s All-Star rosters for Miami. Eighteen Latinos, including replacements for injuries, were selected for the American League and another five for the National League, for a total of 23.

So, close your eyes and listen to the sounds of the game and the language on the field and in the stands. You might think that it’s 1963 and the Polo Grounds all over again.

Featured image: National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum