Fernando Valenzuela: Uniting nations

During the summer of 1957, a Little League team from Monterrey, Mexico, won the Little League World Series in Williamsport, Penn. On Aug. 27, 1957, these youngsters – mostly from disadvantaged homes in an industrial area of town – were honored guests of President Dwight D. Eisenhower in the White House.

Twenty-four years later, Fernando Valenzuela, another baseball player from Mexico, visited the White House as a guest of President Ronald Reagan following a craze that had swept over the United States and Latin America called “Fernandomania.”

They both were beautiful, incredible experiences beneficial to these bordering countries. Baseball was, indeed, the common denominator. In the same unexpected way this Little League team, which did not always have even a real baseball to play with, would walk and hitchhike their way to a Little League World Series title, destiny would thrust another unlikely figure into the forefront while uniting fans from all walks of life.

Born in a humble home in Etchohuaquila, Navojoa, Sonora, on Nov. 1, 1960, Valenzuela arrived on the Major League Baseball scene on Sept. 15, 1980, with the Los Angeles Dodgers.

He was discovered by Dodgers scout Corito Varona and signed by his colleague Mike Brito, both Cubans. To this day, they are both commended for paving Valenzuela’s highway to success.

During the Puerto Rican Winter League’s 1980-81 season, I asked pitcher Gil Rondon, who had played in Mexico that summer, about Valenzuela.

He recalled, “That kid is genuine. He may not overpower the hitters but he has other pitches, among them a deadly screwball. He is young (20), humble and friendly. The Dodgers got a good prospect in him.”

On Saturday, May 19, 1981, I first spoke to Valenzuela, who was with the Dodgers in Shea Stadium. I clearly recall that coach Manny Mota and stellar Spanish play-by-play broadcaster for the team, Jaime Jarrín, set up the phone interview.

The first thing he told me in Spanish was, “Like any kid back home, I first played baseball over rough terrains. Since then, I have dreamed of buying my parents a home. The floor at our house was bare dirt.”

When asked about his record of seven wins – no losses and an ERA of 0.79 at the time, he projected humility while giving credit mostly to the Dodgers.

I first spoke to him in person during the 1981 World Series at Yankee Stadium. His presence immediately impacted me for being so young and performing so well. I saw in him a down-to-earth individual with some difficulties speaking English, against the backdrop of one of MLB’s most hallowed baseball grounds.

During our conversation, it became clear to me that this craze that had taken over MLB that year was a movement millions of fans wanted to be a part of. It was a little something called “Fernandomania.”

What was Fernandomania?

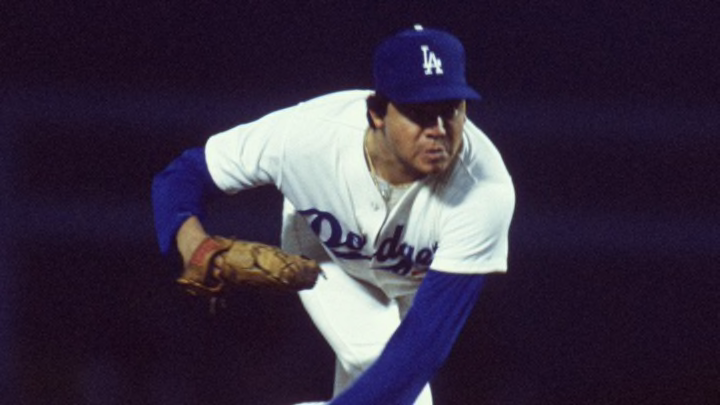

When this young icon would take the mound he would captivate those watching with his peculiar and exciting pitching style where he would look up to the sky seconds before throwing each pitch. He captured the attention of fans everywhere with the dazzling start of his career.

Latino fans everywhere, but especially in Los Angeles, truly identified with him and saw him as a young member of their family who they wanted to look after and cheer on. It was a way of bringing together people to be a part of something bigger than themselves. To me, that was Fernandomania.

Weeks later, Valenzuela became the recipient of the National League’s 1981 Rookie of the Year and Cy Young Awards.

During his career from 1980 through 1997 he was a National League All-Star six times while registering a 173-153 win-loss record with a respectable 3.54 ERA. He played for the Dodgers, California Angels, Baltimore, Philadelphia, San Diego and St. Louis.

Among his career highlights, on June 29, 1990, as a Dodger, he threw a no-hitter against St. Louis and became the first Mexican pitcher to accomplish such a feat.

Coincidentally, earlier that same day, right-hander Dave Stewart of the Oakland Athletics threw a no-hitter against the Toronto Blue Jays. It’s been rumored that Fernando said to his teammates prior to his start that day, “You just saw a no-hitter on TV, now you will see one in person.”

The magic of Valenzuela in MLB made the game bigger in Latin America and elevated it to a higher level internationally.

Besides the pride of being a member of the 1981 World Series champion Dodgers, he also was honored as a special guest of President Reagan in the White House on June 8 of that year along with Mexican President Jose Lopez Portillo.

The Mexican Bull

“El Toro Mexicano,” honored by his country’s baseball Hall of Fame in 2014, is still affiliated with the Dodgers in their Spanish broadcasting team led by Jarrin.

He has also been a staple in coaching Mexico’s team in the World Baseball Classic.

The last time I spoke to him in Texas, with a wide smile, he responded to my question on that topic we had discussed so many years ago, “Yes, thanks to God, I was able to by my parents a home,” he said.

Authentically modest, when he was “on” there was no one better on the mound during his days of glory. His legacy will inspire future generations of players as well as fans everywhere the game is known.

Featured Image: Bettman

Inset Image 1: Courtesy of the Los Angeles Dodgers

Inset Image 2: Luis Rodriguez-Mayoral