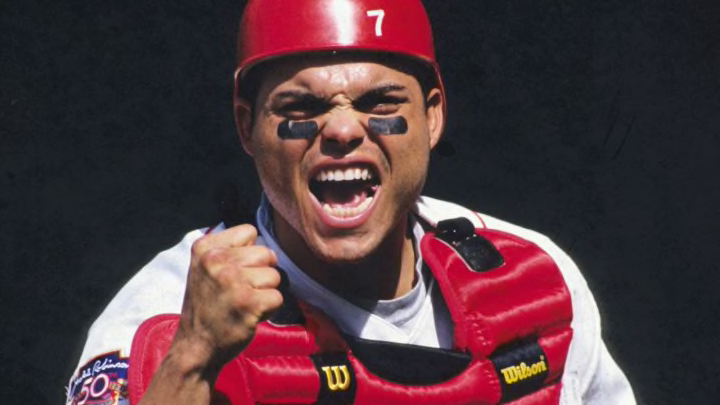

The first time I saw “Pudge” Rodríguez

“To play this game good, a lot of you has to be a little boy.” — Roy Campanella, Brooklyn Dodgers catcher

Coincidentally, that’s how I think of Iván “Pudge” Rodríguez: forever young on the baseball diamond. A teenager who played his first Major League Baseball game at 19 and blossomed into a star so great that he will soon be enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. A kid from a small town whose passion, exuberance and commitment to becoming a better catcher earned him his own plaque alongside Roy Campanella, his boyhood hero Johnny Bench, and Puerto Rico’s national hero, Roberto Clemente.

When I first saw Pudge, I was working for the San Juan Senators of the Puerto Rican Winter League in 1989. He was not quite 18. We were getting ready to play his team, the Caguas Criollos, and I was down on the field watching pregame warmups. There he was, snapping throw after throw with precision and bazooka-like force. All of us stood there in awe of the teenager before us.

I’ve known Pudge for nearly three decades now, including when I worked for the Texas Rangers for eight seasons in the 1990s during his tenure with the team.

I admire how genuine and, yes, boricua, Pudge has always been, even while using his cannon arm to nail anyone oblivious enough to wander off the bag or daring enough to try to steal bases. Born in Manatí and raised in Barrio Algarrobo in the neighboring town of Vega Baja, Pudge always credits his father, José, for inspiring him as a person and ballplayer. He also often professes love for family, especially for his mom, Eva, and his older brother José.

Several moments are impressed in my mind that always remind me of his talent, work ethic and willingness to learn.

A catcher does not make headlines

During the 1992-93 offseason, I was riding in a golf cart in Miami with an old friend, Gary Carter, another catcher who would make it to the Hall of Fame. Gary asked me to relay a message to Pudge: “You can be the best catcher in the game. Play hard at all times and utilize your abilities wisely.”

“A catcher does not have to make headlines every day. As a matter of fact, if nobody talks about you after a game, it means that you did your job.”

And as we all saw, Carter’s advice resonated deeply with Pudge.

Since my earliest days with the Rangers, I always told Pudge that as he acquired discipline as a hitter, he would become great offensively and that the home runs he wanted so much would come naturally. Through the years, I saw Pudge progress under the guidance of hitting coaches Tom Robson, Willie Upshaw and especially Rudy Jaramillo, the best of his generation.

Pudge handled the public with great expertise, becoming both showman and philanthropist. In Texas, he once went for a foul ball in the stands. He did not catch it. But before returning to his spot behind the plate, he reached out with his right hand and took some popcorn from a kid. The fans loved it. Similarly, he won their favor through his work in the community.

cultural challenges

Pudge faced numerous cultural challenges as a young player. When he first reported to the minor leagues in 1989, he arrived at Miami International Airport, alone and with minimal knowledge of English. Just 17, he had no clue how to make the connection to his destination. Disoriented and sad, he found himself sleeping behind a counter overnight. Early the next morning, a Spanish-speaking airport employee assisted him in getting on the plane to Pompano Beach.

Thus, began the historic career of Pudge.

There were memorable trips along the way. During one winter evening in the late 1990s, Pudge invited me to watch a softball game between some of his relatives and a local bakery in Vega Baja. The field was quite a sight. A horse was grazing in right field. Home plate was surrounded by a deep pit. You could see smoke coming out of a hole in the ground in center field, which locals believed was of volcanic nature. And Pudge was the only one in shape. The All-Star played as intensely and enthusiastically in that rundown park as he did on any perfectly manicured major league field, even as his team lost by some 10 runs.

I saw the teenager grow into a man, one who made us Puerto Ricans proud, who followed Clemente’s humanitarian example in the community, who kept the boyish twinkle in his eye when meeting others and traveling the world. I will never forget being with Pudge and Juan “Igor” González when they went to Harvard or met and chatted with Rosa Parks, the legendary human rights activist, in Detroit during the 1998 season. Or two years earlier, touring Japan with MLB All-Stars and seeing how these two great players were so surprised at how much Japanese fans adored them.

I haven’t seen Pudge for some years now. However, I will never forget him and will always be proud of his accomplishments.

One enduring image I have of Pudge remains in what I once told friends: “When the game begins, Pudge is in Heaven… in the dirt that lies behind home plate.”

Truly a catcher for the ages.

Featured and inset image: Craig Jones / Getty Images Sport