Cha Cha: a big hit from the start

By Adrian Burgos

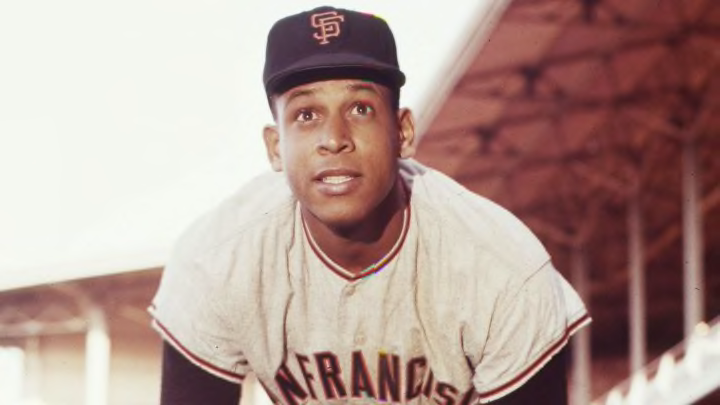

Orlando Cepeda was blessed with broad shoulders and a strong build. He needed them, not just to make it as a baseball player but to also carry the weight of his surname.

When he landed in Florida for a minor-league tryout with the New York Giants in 1955 as a 17-year-old, he carried the Cepeda baseball legacy on his shoulders.

Orlando Cepeda was fully aware of his baseball lineage. His father Pedro “Perucho” Cepeda was a baseball legend well before Orlando suited up professionally. Caribbean fans would regale listeners with stories about Perucho Cepeda’s feats, how he was nicknamed “Babe Cobb” for his power and playing style, and his stellar play in Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, and Venezuela.

Fans expected a lot from Perucho’s son for him to even approximate the level of greatness they ascribed to his father.

The Path Taken

Orlando Cepeda did something his father never did in his professional career. He left Puerto Rico to pursue professional baseball in the contigious United States. That decision put the son on a different track than his father.

Pedro Cepeda had refused to play in the United States when Negro League teams tried to recruit him in the 1930s and 1940s. He had heard too many stories about the indignities of racial segregation and Jim Crow practices that black players endured in the States.

Hearing those stories directly from legendary figures such as Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige, and other African Americans who played in Puerto Rico and other Caribbean leagues was enough to convince the elder Cepeda not to venture north.

The baseball world had changed by the time the younger Cepeda opted to pursue professional baseball in the United States. Jackie Robinson had already initiated the dismantling of organized baseball’s color line in 1947. Minnie Miñoso had become a star as an Afro-Latino in Major League Baseball.

Cepeda’s showing at the Giants’ minor-league camp in Florida was impressive enough to secure a minor-league assignment. He soon encountered the racial realities of life in the U.S. when he was assigned to Salem, Va., and Kokomo, Ind., in 1955. He did not let segregation or its vocal supporters deter him.

The Puerto Rican slugger quickly worked his way up the farm system. Cepeda blossomed in 1957 with the Giants’ top farm team in Minneapolis. He batted .309 with a .852 OPS, hitting 25 home runs and driving in 108 runs. The organizational brass looked forward to a future where the powerful Puerto Rican would join the big league team.

New Beginnings

The 1958 season would be the first of its kind in MLB history. The relocation of the New York Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers to California meant MLB would start its first campaign with teams west of St. Louis.

The Giants started their new era in San Francisco with significant holdovers from their Polo Ground days. Key among these Giants mainstays was superstar Willie Mays. There was also an influx of young talent, including Cepeda, Jim Davenport and Willie Kirkland.

MLB opened the new era with the two former New York City-based teams facing off in San Francisco on April 15. The Giants’ new ballpark was Seals Stadium, long-time home of Pacific Coast League teams.

The Giants enjoyed a dominating performance over their archrivals, defeating the Los Angeles Dodgers 8-0. An above-capacity, sell-out crowd of 23,448 came through the turnstiles for the day game at Seals Stadium, which had capacity expanded to nearly 23,000.

San Francisco made quick work of Dodgers ace Don Drysdale. Powered by a two-run homer by Spencer in the fourth, the Giants chased Drysdale in the fourth inning.

While Drysdale was totally ineffective in giving up six runs in just 3 ⅔ innings, Giants starter Rubén Gómez lived up to his nickname, El Divino Loco, or the Divine madman.

Gomez, a Puerto Rican left-hander, was effective and wild in throwing a shutout despite giving up six hits and walking six. Cepeda, who batted sixth in the lineup, was unable to join the Giants’ hit parade against Drysdale. He was hitless in two turns against the hard-throwing, eventual Hall of Famer.

Cepeda welcomed the entry of Dodgers reliever Don Bessent into the game, blasting a solo home run off him in the fifth inning. The homer would be his lone hit in five turns at the plate.

A Giant in San Francisco

The Opening Day victory and Cepeda’s debut were positive signs for the 1958 campaign. The Giants would earn a third-place finish with a 80-74 record that was a marked improvement from their woeful 1957 season.

Equally important was the production of young talent like Cepeda.

The powerfully-built Puerto Rican batted .312/.342/.854 OPS with 25 home runs, 96 RBI and 15 stolen bases.

Cepeda received all 21 first place-votes from the Baseball Writers’ Assocation of America to become the first Puerto Rican to earn the National League Rookie of the Year Award. Perucho’s son demonstrated that he alsoo would be a giant in baseball. He was more than capable to carry the Cepeda baseball legacy into a new era.

Featured Image: Transcendental Graphics / Getty Images Sport