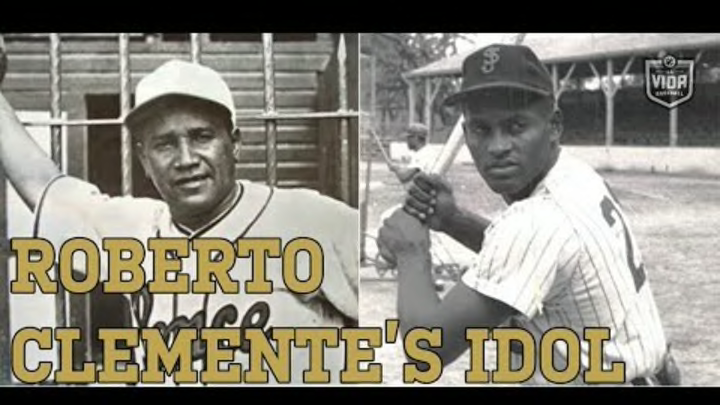

Pancho Coimbre: Clemente mentor and underappreciated legend

Francisco Luis “Pancho” Coimbre came from an era in which films were black and white, and records were inaccurate or incomplete. To get a sense of his aura and skills, you have to trust in the words of legends like Roberto Clemente.

“They say I’m a good player. But he was better than me,” Clemente told me time and time again — this, from a man who batted .317 in an 18-year major league career. Though Coimbre stood 5-foot-8, three inches shorter than Clemente, there was no doubt about his stature on the diamond.

The Puerto Rican Coimbre was an extraordinary hitter who rarely struck out, and an outfielder with great range, sure hands and a good arm.

Because of his dark skin, Coimbre never made it to the majors, but he scalded the ball everywhere else. From the late 1920s through the ’40s, he played in seven different countries with a wide assortment of amateur, semi-pro and professional teams, including the New York Cubans of the Negro Leagues, where he was known as Frank Coimbre.

John Holway, former chairman of SABR’s Negro Leagues Committee, calculated that Coimbre hit .377 in the Negro Leagues, the fifth-best average all-time.

Over 13 winters in Puerto Rico, Coimbre hit .337 with only 29 strikeouts in 1,915 at-bats — and supposedly didn’t whiff once over the course of three seasons in the early ’40s.

Which is why he is remembered as one of the island’s greatest players ever — and one of the best outfielders you’ve never heard of.

In Puerto Rico, where he played for the Leones (Lions) de Ponce starting with the inaugural winter league season of 1938, they called him El Pundonoroso — The Honorable One.

Coimbre twice hit .400 in the Puerto Rican winter league, including .425 during the 1944-45 season, and he was selected to the All-Decade Team of the 1940s.

In his five seasons with the N.Y. Cubans in the ’40s, his skills at the plate impressed even Satchel Paige, the fabled Negro League pitcher enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

“Coimbre could not be pitched to. No one gave me more trouble than anyone I ever faced, including Josh Gibson and Ted Williams,” Paige famously said.

Influential late bloomer

Coimbre was born in Coamo, a small town in the south-central mountains of the island in 1909. He grew up playing sandlot ball and didn’t play on his first organized team until high school. But by age 18 he was playing abroad, first in the Dominican Republic and then in Venezuela.

He was close to my mother’s family in Ponce, so I met him as a child in the early 1950s. He never got a college education, found wealth or held titles, but many of us remember Coimbre as a man who contributed immensely to the growth of Roberto Clemente — both the man and the future Hall of Famer.

Coimbre had spent the early years after his retirement scouting Puerto Rico for the Pittsburgh Pirates. The team took advantage of the Rule 5 draft to claim Clemente in November of 1954 from the Brooklyn Dodgers. Pirates general manager Joe L. Brown and legendary scout Howie Haak wisely encouraged Coimbre to mentor the young and superbly talented 20-year-old outfielder.

Clemente felt an eternal appreciation for Coimbre’s guidance. He credited Coimbre for educating him in how to behave, how to deal with the media and the importance of personal appearance.

In my world of memories, I frequently see Coimbre and Clemente dressed in coat and tie, rarely in casual wear. Watching Coimbre, I saw the posture of a statesman with distinguished enunciation, sharing the rich and wise experiences of his life with others.

Roberto was fortunate to have had a true friend in Coimbre. During the summer of 1988 — a year before his death — Coimbre remembered Clemente in an interview for my radio show in Puerto Rico.

“Late in the 1960s, Roberto invited me to spring training in Fort Myers, Fla.,” Coimbre said. “He took me everywhere, introduced me to everyone. He did it with such pride. I was astonished. There I was, with perhaps the best player in the world, and he was treating me like a king.”

Another time, Coimbre heard rumors that the Pirates wanted to get rid of his services.

With a smile, Coimbre recalled a phone call from Clemente.

“He told me not to worry, because he told Joe Brown that if I got fired, there was going to be a big problem between them,” Coimbre said.

Even now — 45 years after Clemente’s death and 28 years after Coimbre’s — it’s so easy to remember the dedication, righteousness and good will of both men.

They played the game with both grace and ferocity, yet they were well-mannered, soft-spoken and possessed great social consciousness.

In a 1992 conversation with Steve Wulf, who at the time wrote for Sports Illustrated, I recalled a strange connection between Coimbre and Clemente.

Clemente got his 3,000th hit on Sept. 30, 1972 in Pittsburgh. During the next day’s pregame ceremonies, we presented Roberto with a special award containing a clod of earth from the field in Puerto Rico where he had played baseball as a kid.

A picture had gone out over the news wires and upon looking at it, I noticed a sadness to his face. A few days later, at my home in Puerto Rico, I showed the picture to Coimbre and he sternly said, “This man is dead.”

Three months later, his premonition unfortunately came true, when the plane Clemente was on to get supplies to an earthquake-ravaged Nicaragua crashed after takeoff on New Year’s Eve.

Late in his life, away from the game, the crowds and the great ovations, almost up to the day of his death, Coimbre sold lottery tickets to meet his humble needs. Such is life.

Coimbre died in a fire at his home, at Calle Estrella 8 in Ponce, late one Saturday night in November 1989. He was 80 years old.

In 2006, he was one of the 94 players initially considered by the Hall of Fame’s Special Election Committee on the Negro Leagues and pre-Negro Leagues. However, he failed to make the first cut and missed his chance to enter Cooperstown.

Nonetheless, he remains celebrated elsewhere. Coimbre was enshrined in the Puerto Rican Sports Hall of Fame in 1959 and posthumously in the Puerto Rican Baseball Hall of Fame in 1991. And in 2010, he was honored by the Latino Hall of Fame in the Dominican Republic.

As time goes by, I fear that Coimbre’s legendary talent will be lost to history, and the man forgotten. But those who knew him will recall above all his tender smile, his kindness and his humility. I suppose, too, that Clemente would have remembered him in a similar way.

Inset Images: Luis Rodriguez Mayoral