Puerto Rico: Small Island, Hall of Fame Legacy

Roberto Clemente, say no more.

Orlando Cepeda, a true “Baby Bull” in his prime, a feared slugger who was the first Latino to lead either circuit in home runs and RBI.

Roberto Alomar, smooth as silk, a two-time World Series champion second baseman.

Three giants, bronzed in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, elegant players all part of a select group in Cooperstown.

Puerto Rico may not have the storied history of Cuba, where professional baseball took root in 1878 and where the warm winters drew all-star barnstorming teams for decades afterward.

And it may not produce as many superstars as the Dominican Republic and Venezuela, two countries that together could fill the rosters of seven major league teams right now.

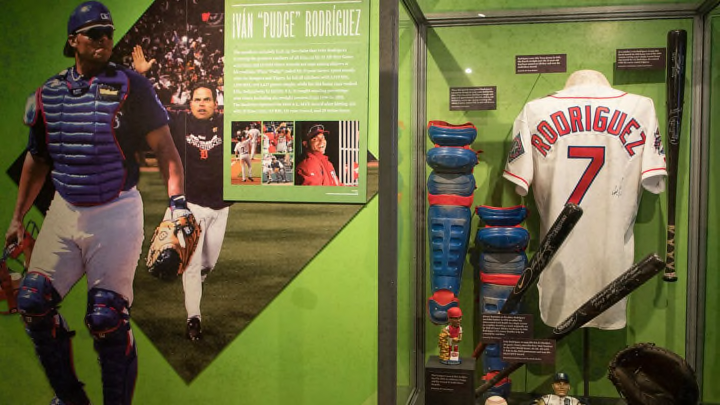

Yet for a tiny island of 3.5 million people, Puerto Rico punches well over its fighting weight. When Iván “Pudge” Rodríguez is enshrined this weekend, he will be the fourth boricua inducted — and just the 13th Latino overall.

While took until 1938 for Puerto Rico to launch a professional baseball league, long before that it was played at the local level, town against town — a nurturing tradition that still endures today through the island’s amateur structure, known in Spanish as Béisbol Doble A. The season runs from mid-February to September and teams play Friday, Saturday and Sunday. My ’hood against your ’hood.

“Why is baseball so important to the island’s social fabric? The answer is very simple: pura pasión. Pure passion,” said Ángel Colón, a historian based in San Juan who is completing a book about Puerto Rican baseball. “Baseball is our life. We are devoted to the game. We take enormous pride in it.”

“What Clemente, Cepeda, Alomar and Pudge share — what all the players from Puerto Rico have in common — is their dedication to the game, a commitment to excel and, above all, to win,” Colón said.

No Escaping Jim Crow

The island’s four Hall of Famers represent a powerful legacy, a royal lineup of players who predate Clemente. Early Puerto Rican stars remain largely unknown outside the Caribbean. They were too good to be ignored by scouts, yet too dark to play in the major leagues. Because they could not escape the color line that divided professional baseball, these pioneers displayed a tenacious will to play as they tried their luck in other countries and leagues, including the Negro leagues.

Foremost among them was Emilio “Millito” Navarro, a patriarch of the game on the island.

A diminutive infielder who stood barely 5-foot-5, he left a giant imprint all over the Caribbean. The first Puerto Rican to star in the Negro leagues, Millito played for the Cuban Stars in 1928 and 1929. Known for his blazing speed and soft hands, his hitting stats are incomplete because most Negro league statistics were unrecorded. But before Alomar, there was Navarro.

Navarro, who lived to the ripe old age of 105 before passing away in 2011, was blessed to see all who followed in his footsteps. That includes Francisco “Pancho” Coimbre, one of the best outfielders in Latin America, and maybe anywhere.

Coimbre was the top Puerto Rican League star of the late ’30s and through the ’40s, winning five championships in 13 seasons with los Leones de Ponce (Ponce Lions) and earning accolades with various teams in the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Mexico, Colombia and Canada as well as with the Cuban Stars.

A superb contact hitter, Coimbre never got to the major leagues because of his dark skin. Clemente insisted Coimbre was the better player. Though his stats are also incomplete, John Holway, former chairman of SABR’s Negro Leagues committee, calculated that Coimbre hit .377 in the Negro Leagues, the fifth-best average all-time. In Puerto Rico Coimbre hit .337 with only 29 strikeouts in 1,915 at-bats — and supposedly didn’t whiff once over the course of three seasons.

Satchel Paige, the fabled Negro League pitcher enshrined in the Hall of Fame, gave Coimbre the highest of marks. “Coimbre could not be pitched to. No one gave me more trouble than anyone I ever faced, including Josh Gibson and Ted Williams,” Paige once said.

Then there was Pedro “Perucho” Cepeda, the father of Orlando and the original “Bull” in the family. Perucho played from 1928 to 1950, hitting .400 in the Dominican Republic and tearing up the Venezuelan league numerous times. He’s the only Puerto Rican to hit .400 in the island’s Winter League at two different positions: shortstop and first base.

He was so admired that he was considered the Puerto Rican Babe Ruth and was even called “Babe Cobb” for his fierce hustle.

Álex Pompez, the Cuban-American executive enshrined in the Hall of Fame who ran the Cuban Stars and later the New York Cubans, tried repeatedly to sign Perucho. Cepeda stood resolute in his refusal to come to the States because he abhorred racism and didn’t want to submit his family to racial segregation.

Major League Breakthroughs

Ironically, before Jackie Robinson broke the color line, Latinos bent it with their range of skin tones and their “foreign” status. Some wondered whether major league organizations were manipulating racial barriers to permit “brown” Latinos but not African-Americans.

It was in this setting that Hiram Bithorn, a sturdy right-handed power pitcher, made his big-league debut with the Chicago Cubs on April 15, 1942.

“It’s important to note that he was white, very white,” his biographer, Jorge Fidel López Vélez, wrote in La Vida Baseball in March. “And his last name sounded Anglo-Saxon. Bithorn was white, had the right last name and had talent. All that helped him get his first contract.”

Bithorn may have been the right Puerto Rican at the right time, but like other black and Latino pioneers, he was obliged to be better than average. He’s never been fully recognized, despite winning 18 games for the Cubs in 1943 and leading the National League that season with seven shutouts.

WWII interrupted Bithorn’s career the following year, and he played only two more major league seasons upon his return from the war. And then his life was cut short — while training to become a major league umpire, says López Vélez, Bithorn was shot to death by a policeman during a trip to Mexico in 1951.

Luis Rodríguez Olmo came right after Bithorn, debuting the following season on July 18, 1943 with the Brooklyn Dodgers. A slender hitter and splendid outfielder who perfected his craft in seven different countries and in so doing earned one of the better sobriquets in baseball, El Pelotero de América, or the Americas’ Ballplayer. Olmo’s breakthrough was remarkable in more ways than one.

“In the days before Jackie Robinson broke through with the Dodgers, Olmo was the first non-white that American Dodgers fans embraced,” noted La Vida Baseball Editor-in-Chief Adrian Burgos Jr. in a tribute to Olmo following his death on April 28.

Olmo was quite the artist with his glove and had matinee-star looks, according to the press reports of the day. He perfected basket catches before Willie Mays, and Clemente always credited Olmo for teaching him the art of catching the ball at his waist.

In 1945, Olmo emerged as a formidable part of the Dodgers’ starting lineup with his all-around game. Playing left field, he drove in 110 runs with 27 doubles and 10 home runs while leading the National League with 13 triples.

But when team president and general manager Branch Rickey refused to negotiate a better salary for the following season, Olmo jumped along with others to the new Mexican League being started by millionaire Jorge Pasquel, and was temporarily banned from MLB.

Yet his imprint is not for jumping leagues. Rather, Olmo was the first Latino to hit a home run in the World Series, during the Dodgers’ loss to the New York Yankees in 1949. And in his long career as a player, manager, broadcaster and scout, he inspired succeeding generations, including Pudge Rodríguez, who wrote a tribute in social media after Olmo’s passing.

Integration Pioneers

After Robinson, the doors opened for players of all colors, and the trickle of Latin American pioneers turned into small waves.

In the mid-1950s, a generation of Puerto Ricans broke through that included Clemente, Cepeda, pitchers Juan “Terín” Pizarro and Rubén Gómez, first baseman Víctor Pellot (Vic Power), and infielder Félix Mantilla, who with Hank Aaron and others broke the color line in the South Atlantic League.

Cepeda was the unanimous choice for Rookie of the Year in 1958 and was the National League MVP in 1967. Pellot changed the way they played first base, casting a wide net with his glove and winning seven consecutive Gold Gloves. A smooth infielder, Mantilla helped Aaron and the Milwaukee Braves win the World Series in 1957, when they beat the Yankees in seven games.

Clemente, of course, went on to win four batting titles, 12 Gold Gloves and two World Series titles while becoming the first Latino to reach 3,000 hits. He matched the standards set by his idols Coimbre and Olmo in his passion for the game.

The Modern Era

Clemente’s generation begat players such as Félix Millán, Willie Montañez, Santos “Sandy” Alomar Sr. and Iván de Jesús, infielders with excellent gloves and decent bats. Such as the Nuyorican lefty John Candelaria, the second Latino to throw a no-hitter. And reliever Willie Hernández, voted the Cy Young Award and the AL MVP while leading the Detroit Tigers to the World Series championship in 1984.

The flow of talent ebbed and flowed over the following decades, but Puerto Rico’s best players were almost always among the best major leaguers. Alomar had two sons, Sandy Jr., a six-time All-Star catcher, and Roberto, the future Hall of Famer.

Meanwhile, Texas Rangers scouts Luis Rosa and Omar Minaya set up shop in Puerto Rico and began mining for talent. Besides Pudge, they signed outfielder Juan “Igor” González, a two-time MVP who hit 434 career home runs.

In the ’90s Jorge Posada and Bernie Williams helped reignite a pinstriped dynasty while another Nuyorican, Edgar Martínez, elevated the position of DH, hitting .312/.418/.933 over 18 seasons. There were also three Carloses: Baerga, Delgado and Beltrán.

The island saw a drop-off in major league talent when its players were included in the annual amateur draft in 1990. But after back-to-back trips to the World Baseball Classic finals and the rise of a new generation led by talented youngsters including the Astros’ Carlos Correa, the Cubs’ Javy Báez and the Indians’ Francisco Lindor, the game has regained firm footing on the island.

And now this weekend, Puerto Rico gets ready to celebrate one more bronzed giant in Cooperstown. When it comes to baseball in Puerto Rico, size doesn’t matter. It is, and always has been, an island of giants. And Hall of Fame players.

Featured Image: Milo Stewart Jr. / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Inset Image: Jorge Fidel López Vélez