Clemente’s dream: first black manager

Roberto Clemente was a man of many firsts. First Latino to 3,000 hits. First Latino in the Hall of Fame. First in the hearts of many baseball fans.

But you probably didn’t know that Clemente aspired to become the first black manager in major league history. He wouldn’t have been the first Latino, since that honor goes to the Cuban Miguel “Mike” González, who briefly managed the Branch Rickey-led St. Louis Cardinals in the late 1930s.

Clemente, while still a major leaguer at age 36, managed the Senadores de San Juan for a full season during the 1970-71 Puerto Rican winter league, going head-to-head against Frank Robinson, another All-Star outfielder who at 35 also had his sights set on eventually becoming the first black skipper.

Their competition is recounted in great detail by Puerto Rican baseball historian Néstor R. Duprey Salgado in his book, Clemente: En la víspera de la gloria (Clemente: On the Verge of Glory), published last year.

Opening Night

After a week of heavy rains and multiple blackouts in the San Juan metropolitan area, Opening Day dawned on Oct. 22, 1970 to great fanfare. Press reports say 30,000 fans showed up at Hiram Bithorn Stadium that night to watch Clemente and the Senadores face off against their intercity rivals, Cangrejeros de Santurce. Robinson was enjoying his third straight season managing the Cangrejeros.

Problems with the stadium lighting delayed the start of the game until 9:50 p.m. In the book, Senadores pitcher Bill Denehy describes a rowdy scene with impatient fans yelling and chanting, throwing beer at each other and playing music. That was just a prelude to a tense meeting between the managers as electricians scrambled desperately to restore power.

“We have to call the game,” Robinson said.

“If we call the game, we are going to have a riot,” Clemente said.

“If we have a riot, we have a riot. I’m not going to have my guys play without that bank of lights,” Robinson shot back.

“That’s your decision. But if you’re going to have the game called, you’re going to get on the public address system and announce it yourself. You’re going to be the one to tell them,” Clemente answered.

“Let me give it another look,” Robinson said. “Let’s throw a couple of pitches. Maybe we can play.”

Clemente’s Miracle

And play they did. Senadores starter Ken Brett, brother of George, struck out Cangrejeros right fielder and future Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson three times as San Juan took an early 2-0 lead. Then another bank of lights went out, at the end of the sixth inning. After talking to umpires and officials, Clemente told his players to warn their families that the game would soon be called because of a midnight curfew and that, for their safety, they should leave the ballpark.

Despite the dim lighting, the game continued. Santurce scored three times in the top of the eighth to take a 3-2 lead. Sure enough, when the game was called shortly afterward, fans began overturning cars in the parking lot and setting them on fire. A riot broke out and, in short order, the National Guard arrived.

Clemente, wanting to prevent further violence, requested permission to speak to the fans. Denehy said that the National Guard commander gave him 10 minutes. Clemente took the PA mike, addressed the crowd in Spanish and, within 10 minutes, the rioting had stopped and the parking lot emptied.

“My teammates and I sat there and marveled. Was he God? Roberto asked all the rioters to go home, and everyone went home. It was like he had separated the waters,” Denehy said.

While Clemente had performed a miracle of seemingly biblical proportions, he did not win his first game, setting the stage for a bittersweet season that placed the revered superstar under a harsh spotlight. It didn’t matter that he was managing his boyhood team, the same club for which he played most of his winter league career.

As he discovered quickly enough, being “Clemente” did not keep him immune from the second-guessing of reporters, broadcasters, fans or even the players themselves.

The Clemente standards

The story of that season is fascinating and complicated, much like the man himself. It was Clemente’s nature to nurture and lead. He’d had two brief experiences in running a team, including as a player-manager for the Senadores in 1964-65, after the team fired Carl Elmer in December.

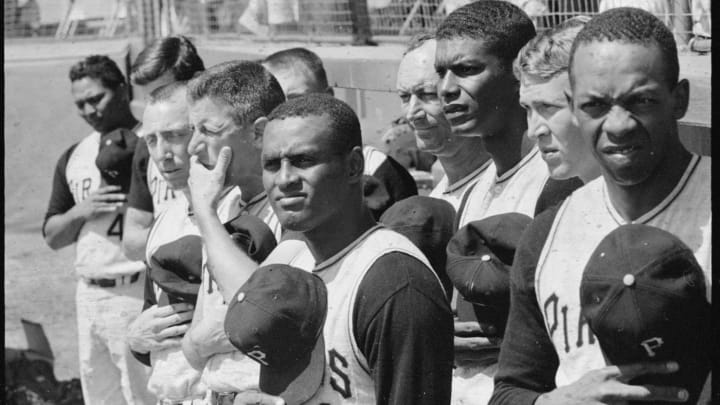

In Pittsburgh, where Clemente and another black player and future Hall of Famer, Willie Stargell, acted as elder statesmen, he held players’ meetings with the total support of management.

Not only did Clemente mentor younger Latinos like Panamanian catcher Manny Sanguillén, he looked out for black players like Dave Cash and Al Oliver. Pittsburgh sports writers speculated that the Pirates saw Clemente as managerial material in due time, though not necessarily as the game’s first black skipper.

But like many superstars who tried a hand at managing, Clemente didn’t always understand why his players didn’t share his drive and work ethic, or why they didn’t execute basic plays consistently.

Clemente judged players as he judged himself — it didn’t matter whether they were an established major league star or a promising prospect in need of playing time.

The Cuéllar Incident

Clemente juggled a Senadores lineup that included fellow Pirates Sanguillén, Cash and Oliver, as well as a cluster of major leaguers: outfielder Ken Singleton, first baseman Mike Jorgensen, shortstop Freddie Patek, third baseman José “Coco” Laboy and pitchers Brett, Jim Lonborg and José “Palillo” Santiago.

That list also included Cuban lefty Mike Cuéllar. An established ace who was part of a brilliant Baltimore pitching staff with Dave McNally and Jim Palmer, Cuéllar was coming off a 1970 campaign in which he notched 24 wins in the regular season and one more in a triumphant World Series against the Cincinnati Reds.

But Clemente wasn’t about to let anyone coast, not even the first Latino to win a Cy Young Award. After a poor start in his second outing of the winter league season, Cuéllar got the hook from Clemente in the fourth inning. A spat that essentially ended Cuéllar’s winter season ensued. According to bench coach Saturnino “Nino” Escalera, Clemente told Cuéllar on the mound: “You are a star, you are a big leaguer; here, you have to show who you are.”

The San Juan Star quoted Clemente afterwards, “If you’re not able to give it all, you shouldn’t be playing.”

“There were times [Clemente] would get frustrated because we didn’t play at the level he expected us to play,” Brett said in an interview with baseball historian Thomas Van Hyning. “I’ll never forget the time he decided to play to prove his points. He was a hero down there. The people went crazy and it helped attendance.”

Clemente and Cuéllar would meet again the following season, as the Pirates defeated the Orioles — and their four 20-game winners — for the World Series championship.

Managing ‘a la americana’

Clemente was willing to hold players, umpires and league officials alike to the same high standards. He also upset established norms, managing a la americana, as the local fans and press quickly labeled his style.

Clemente didn’t wait for starting pitchers to tire out before replacing them. He brought in relievers for specific situations, like lefty versus lefty.

He played “small ball,” asking his batters to bunt, hit and run, and steal bases — the complete opposite of waiting for the big hit, as winter play normally dictated. Clemente loved the suicide squeeze, to the point that opposing teams anticipated it every time a runner got to third.

If Clemente was completely engrossed in the minutiae of the game, he was also stretched thin off the field. Besides numerous receptions and presentations, Clemente was hard at work trying to establish a financial base for his dream project, Roberto Clemente Sports City, in San Juan. He had so many commitments that he would frequently arrive at the ballpark 15-20 minutes before the first pitch.

“He practically would arrive just before game time, completely soaked in sweat. I would bring him up to date on what had been accomplished in the workouts, he would do his lineup and I would hand it to the umpires. He was completely dedicated to baseball,” Escalera told Duprey Salgado.

Scrutiny and debate

Clemente’s methods may have provoked much scrutiny and debate, but they didn’t deter the fans. After the Senadores’ first 36 games of the season, the league reported that attendance had increased by 38,465, to 189,565, in comparison to the previous year. The Senadores were up nearly 20,000 after their first six home games, to 45,043.

Weather played havoc with the season. Constant rains and occasional blackouts postponed numerous games and forced multiple double-headers. To give his pitchers needed work, Clemente added a new wrinkle to his managing tactics — in one game, he used three pitchers for three innings each.

The Senadores hovered around .500 most of the season, chasing the first-place Criollos de Caguas while battling Robinson and the Cangrejeros for second. The Senadores usually won with pitching and timely hitting. When they lost, Clemente frequently blamed it on errors and poor execution.

Clemente was occasionally guilty of poor judgment. In a game against Santurce on Dec. 19, Clemente made contact with the umpire while he and infielder Max “Mako” Oliveras argued balls and strikes. Both were ejected. Clemente was suspended for seven days and fined $100. Oliveras was fined $25.

Escalera took over the team and ended the month of December on a four-game winning streak. Possibly to take the edge off the suspension, the Senadores announced that, upon his return, Clemente would be activated and eligible to play.

‘Giving my soul’

Clemente had said early on that he wanted to focus on managing, but now he was making room for himself on the roster. When local baseball writer René Molina caught up with Clemente right after New Year’s Day, he asked, “Do you like managing?”

“Yes, even though it’s much more complicated than what I thought it would be, and what most of the public thinks it is, especially in a winter league like ours,” Clemente said. “It’s a different kind of challenge… It’s like undergoing an apprenticeship at a hard school. Even though I don’t know whether I’ll pass, I’m trying to succeed the only way I know how to in baseball — by giving my soul.”

With Clemente’s return, the Senadores kept winning, amid all distractions. On Jan. 10, Clemente received his 1970 Gold Glove in a pregame ceremony that included Gov. Luis A. Ferrer, a supporter for statehood. Even though Clemente had openly campaigned for Ferrer’s pro-commonwealth rival in the previous election, politics were discreetly ignored in homage to a public figure. Clemente was indeed bigger than life.

Clemente debuted as a pinch hitter on Jan. 12 against Santurce in the last inning of a double-header with two outs and runners on second and third. Facing Rubén Gómez, Clemente lashed at a low curveball, sending it deep to right field — and straight to Reggie Jackson’s glove, ending the game.

Clemente played regularly the last week of the season and the Senadores finished 37-30, edging Santurce for second place and earning home-field advantage for the semifinals against the Cangrejeros.

Whether that would be an advantage was debatable. Santurce had won the “City Champ” series, 8 games to 4, and Robinson had a powerhouse lineup. Jackson hit 20 home runs with 46 RBI and 47 runs scored in 69 games. And Juan “Terín” Pizarro notched six shutouts while recording a 2.31 ERA.

Even though San Juan took 1-0 and 2-1 leads in the series, the Senadores were unable to hold on. Clemente, nonetheless, left his imprint.

He didn’t play until Game 3, when he pinch-hit with the bases loaded in the top of the ninth, slashing a single to break a 4-4 tie and secure a 7-4 win.

“I had doubts whether to pinch hit because I don’t want my team to think that they depend on me as a player,” Clemente said after the game. “They finished second in the standings by themselves and I want them to win in the playoffs the same way.”

Clemente also didn’t play in Game 4. To the visible dismay of the crowd, he sent Oliveras to pinch-hit for the pitcher in the seventh inning with two men on. Oliveras failed to deliver and Santurce won, 5-2.

Clemente returned to the lineup in Game 5, hitting third and going 2-for-4. In a key play, Jackson threw Clemente out at home when Clemente tried to tag up on a fly to right field. Santurce won, 2-1.

Down 3-2 in the series, Clemente didn’t play in Game 6. He instead started a rookie lefty, Ángel “Papo” Dávila, in an attempt to neutralize Jackson and the other left-handed batters. The fans were so mad that from the start they chanted that Dávila was un regalo — a gift.

Dávila lasted less than two innings, giving up two hits and two runs, and Santurce clinched the series.

Blame game, and a confession

Shortly afterward, Clemente announced his retirement from baseball in Puerto Rico. He said that the team fell short because of injuries, errors and mental mistakes. He also made clear that he was upset with management because it didn’t defend him against vocal criticism.

“No gray hairs, but I lost some hair managing. They wanted to throw me off the island because my club finished second,” Clemente told Charles Finney of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

“A manager, he must be a politician, he must be a psychiatrist. In Puerto Rico, everybody on my team wanted to play. Some, I could tell, were not happy that they did not play,” Clemente told Bill Christine of the Pittsburgh Press.

Christine asked Clemente point-blank: If general manager Lee MacPhail offered Clemente the Yankees job, would he take it?

“I would say no. The first black man to manage, he must be absolutely ready. I am not that ready yet,” Clemente confessed.

As always, Clemente was honest, if not blunt. He finally put managing aside to pursue his goal of 3,000 hits, reaching his dream in 1972 on the last regular-season at-bat of his career. Jackie Robinson, who broke the color barrier in 1947 and openly advocated for a black manager in his later years, passed away weeks later, on Oct. 24. And Clemente died on Dec. 31 on his humanitarian mission to Nicaragua.

But you could say that Clemente’s efforts were not for naught. The honor of the first major league black manager appropriately went to the man who battled Clemente during the 1970-71 winter league season, Frank Robinson. Hired by the Cleveland Indians, he debuted on April 8, 1975.

Robinson went on to manage five teams over 16 seasons, including the Baltimore Orioles, and was voted 1989 AL Manager of the Year. Surely, somewhere, Clemente was smiling.

Featured Image: Library of Congress

Inset Image: Néstor R. Duprey Salgado